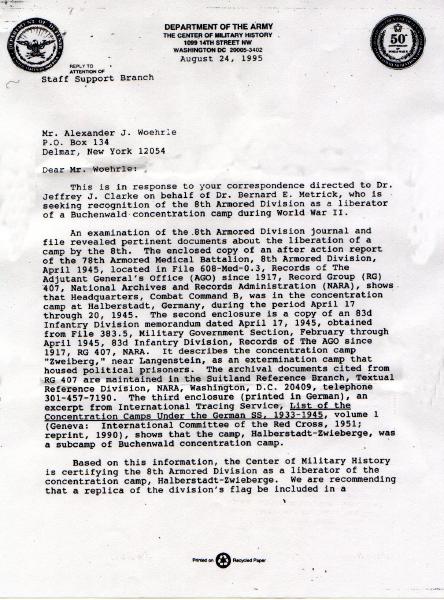

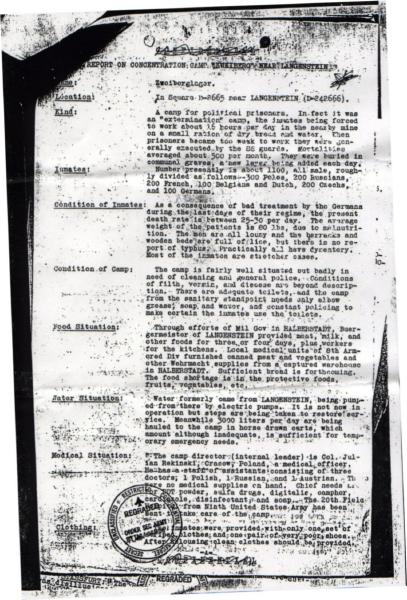

“Between April 12 and 17, 1945, the 8th Armored Division moved into central Germany. There, it liberated Halberstadt-Zwieberge, a subcamp of the Buchenwald concentration camp. The area around the city of Halberstadt housed a number of Buchenwald subcamps that had been established in 1944 to provide labor for the German war effort.

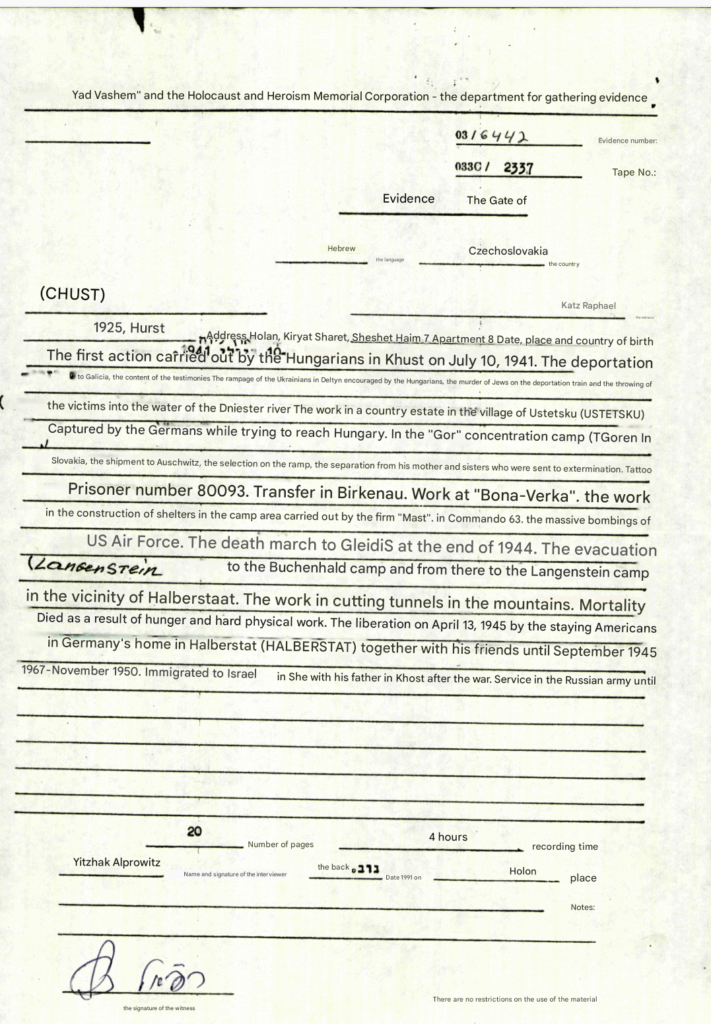

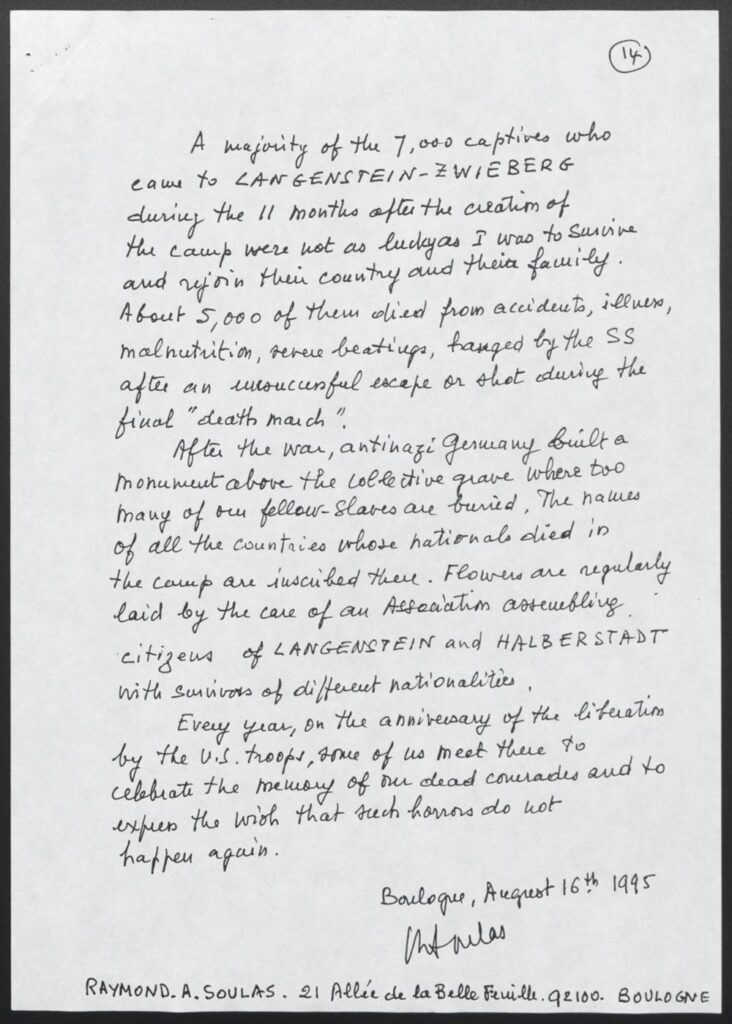

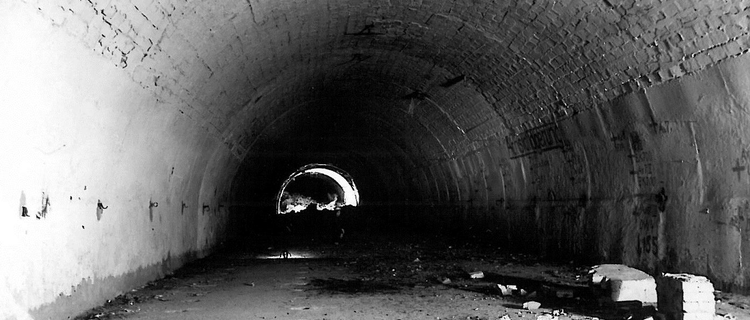

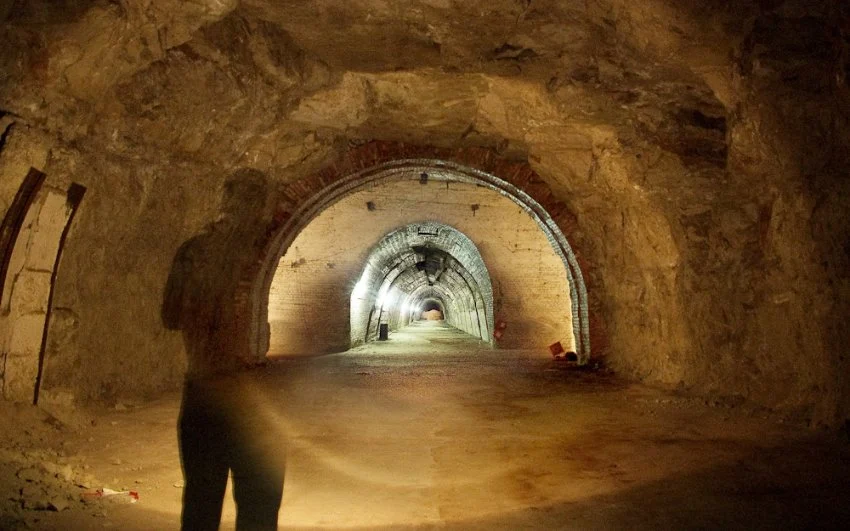

These included Halberstadt-Zwieberge I and Halberstadt-Zwieberge II. These two subcamps held more than 5,000 inmates. These inmates were forced to hollow out massive tunnels and build underground factories for the construction of Junkers military aircraft. The US Army Center of Military History defines a liberating division as one whose official records show its presence at a camp within 48 hours of the first soldier’s arrival. The 8th Armored Division is among the 36 US divisions that have been recognized to date.”[18]

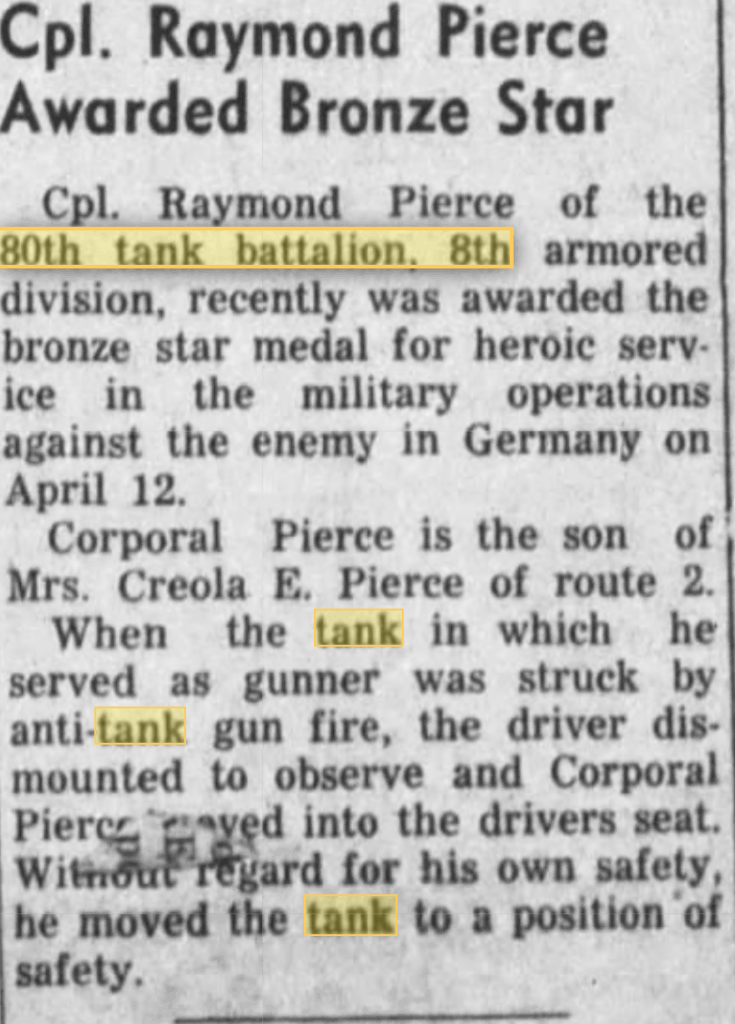

Melvin Maurice “Bud” Allen was born in Goodwine, Illinois in 1925, and enlisted in the armed services in in 1944, went to basic training in Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and joined the 8th Armored Division as a bow gunner in the 80th Tank Battalion, Company A.

This is the story of my grandfather and his division – liberators of the Langenstein-Zweiberg concentration camps.

At the Sound of our Tanks

I had grown up with the legend of my grandfather’s military service, and when I set out to research the history, I often found myself in the uncomfortable position of separating the familial myths from the facts.

For instance, I had always been told that our Grandfather was “in the third wave in D-Day” and that “he had witnessed the aftermath of the battle at Normandy” — but if his honorable discharge papers are to be believed, he was still stateside while the invasion was taking place, and entered France not through Normandy but Bacqueville, 136 kilometers away. At best, he may have seen some destruction near Normandy in passing, but even then, it would have been a year after the massive Allied invasion took place. Nearly every other story, though, I was able to independently verify through division itineraries, after action reports, diaries of men who served in the 8th Armored, as well as a litany of other sources.

PFC Allen’s service record places him in A Company of the 80th Tank Battalion of the 8th Armored Division, and the 80th Tank Battalion was used as a reinforcement unit, designated as ‘Combat Command Reserve” in the 8th’s records. The “CCR” designation is used frequently in the 8th’s after action reports, alongside other task force notations (ex. Task Force Crittendon, Task Force Walker) to describe which units were attached together.

In some documents, Company A of the 80th Tank Battalion was usually attached to CCA, (Combat Command A). Two members of Company A were Silver Star recipients, and, without question, Company A (my grandfather included) were remarkably efficient in combat against the Germans.

“Eleven M-4 tanks had been knocked out, three jeeps had been destroyed, and nine halftracks had been lost due to mines and high velocity fire. Personnel casualties had also been high in the units of CCR. The 58th had suffered 137 killed or wounded and the 80th Tank Battalion had evacuated 66 of its members. Enemy losses counted in the wake of CCR’s advance were six Mark V tanks, 20 mm multiple purpose guns, one large caliber railroad gun, and over three tons of assorted small arms.” [8]

This battle took place in the vicinity of Operdicke on April 12, and could have been the worst fighting my grandfather may have seen during the war. 66 men in his battalion were evacuated, and the 58th suffered 137 casualties. They seized tons of enemy weapon caches, destroyed enemy tanks, and even got their hands on a “large caliber” railroad artillery installation.

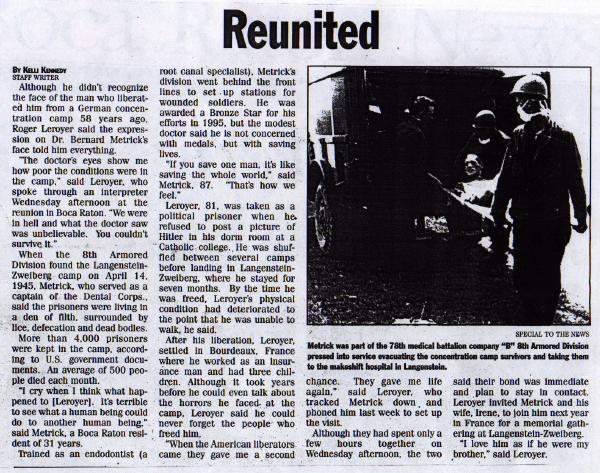

According to the company’s itinerary, the closest they got to Halberstadt or Langenstein was Ströbeck, 8 kilometers (or 4.97 miles) away from the concentration camps. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum says the camp was liberated ‘between April 12th and 17th” but on April 13th, the company was in Hengsen, Germany, while the 78th Armored Medical Battalion was operating in Halbertstadt from April 13th to April 22nd. If Company A saw the camps in Halberstadt-Zweiberg, it was probably April 20th or 21st, since their company itinerary has them arriving in Ströbeck on the 20th, then arriving in Goslar on the 21st.

Let me be clear — the United States has formally recognized the 8th Armored Division as liberators of Langenstein-Zweiberg. That is a better day’s work than I will ever do. That being said, the 399th Field Artillery and the 78th Medical Battalion were the first units to arrive at the camps in Halberstadt, and if the 80th Tank Battalion assisted with the liberation or cleanup of the camps, it was likely indirectly and in a supportive role of the medical units who had discovered the site several days earlier — as they were only within roughly 5 miles of the camp on April 20th, 1945.

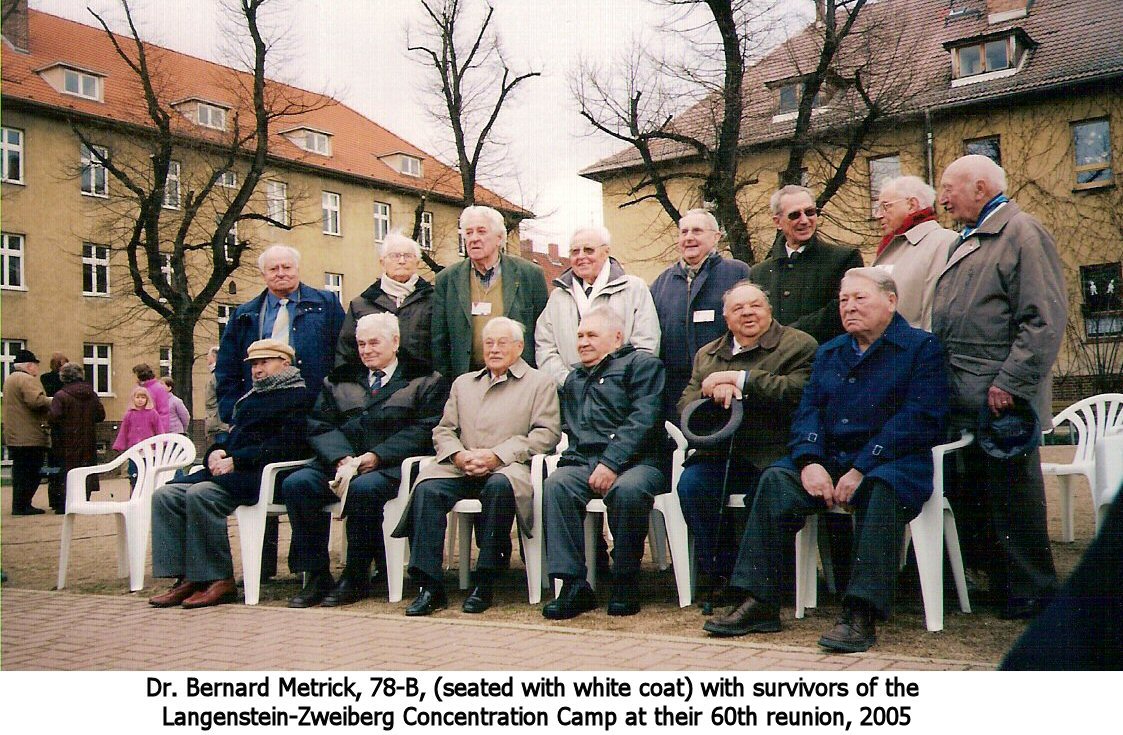

To me, the most poetic description of the 8th Armored’s role comes from the survivors who told one of their first liberators, Dr. Metrick, that the mighty roar of Allied tank tracks in the distance were enough to make their cowardly captors flee. The 8th had become Joshua shaking the walls of Jericho:

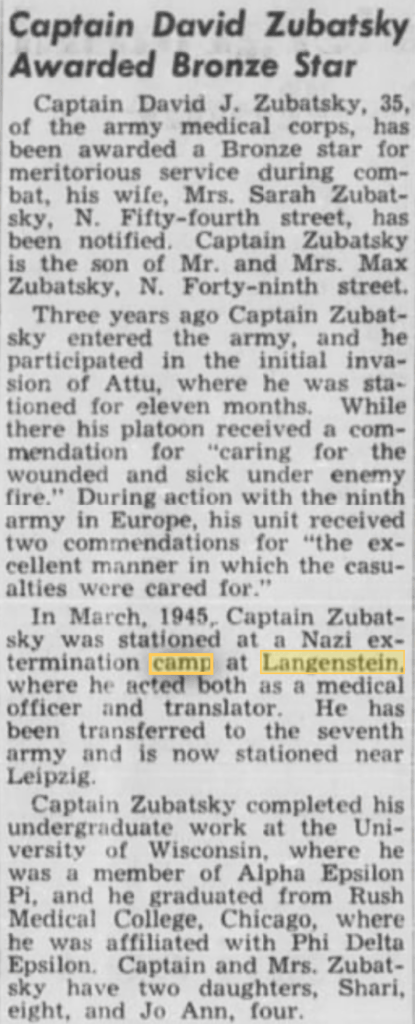

“In April 1945, while battalion surgeon to the 399th Armored Field Artillery, I became, through no special effort of my own, the first Allied officer to enter a slave-labor concentration camp, Langenstein-Zwieberge… They told me that there was a concentration camp nearby and that we could liberate it because, they had heard, the guards had fled. It turned out that the guards had fled two days earlier at the sound of our tanks rumbling down the road. They had demobilized themselves simply by changing into mufti and melting into villages.”[11]

The Camps in Langenstien-Zweiberg

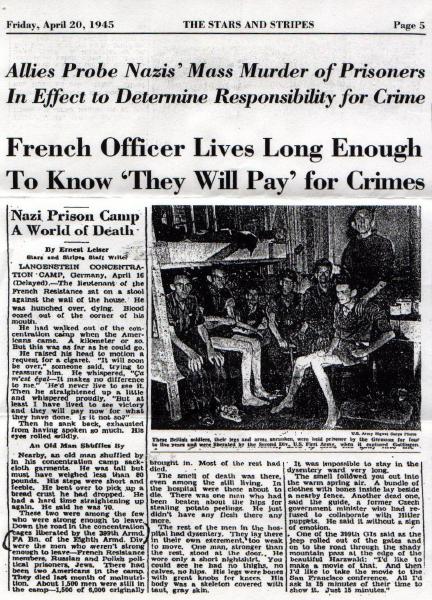

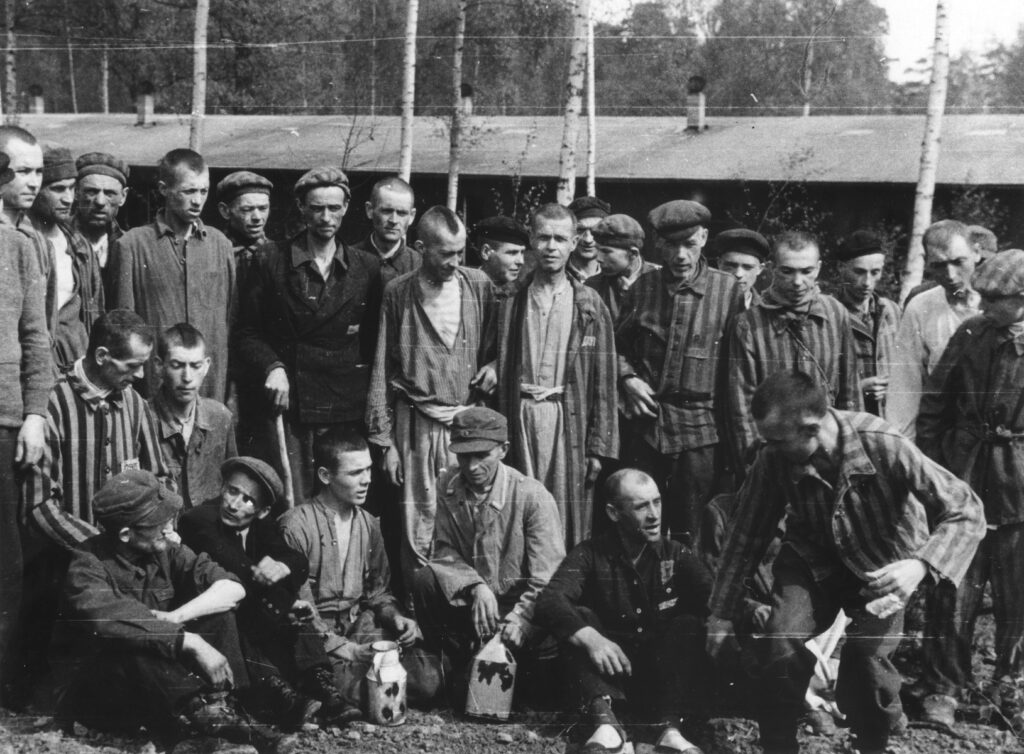

“Arno Lustiger survived the forced march and somehow came to the camp in early 1945 Langenstein-Zwieberge at Halberstadt. Most of the prisoners there had to toil in the vicinity of this secret project “Malachite”. Behind this pseudonym concealed the Nazi plan to build a huge underground facility in order to protect components for aircraft turbines from Allied bombing. “The workers died like flies,” said Lustiger, today a renowned historian. “The average life expectancy in the camp was three to four weeks.” Without protective masks and helmets the internees had to blow up the rock from the rock walls. At five clock in the morning there was roll call, then it was the only meal for the day, then a twelve-hour shift, that killed about 1,900 workers within a year – extermination through work.”

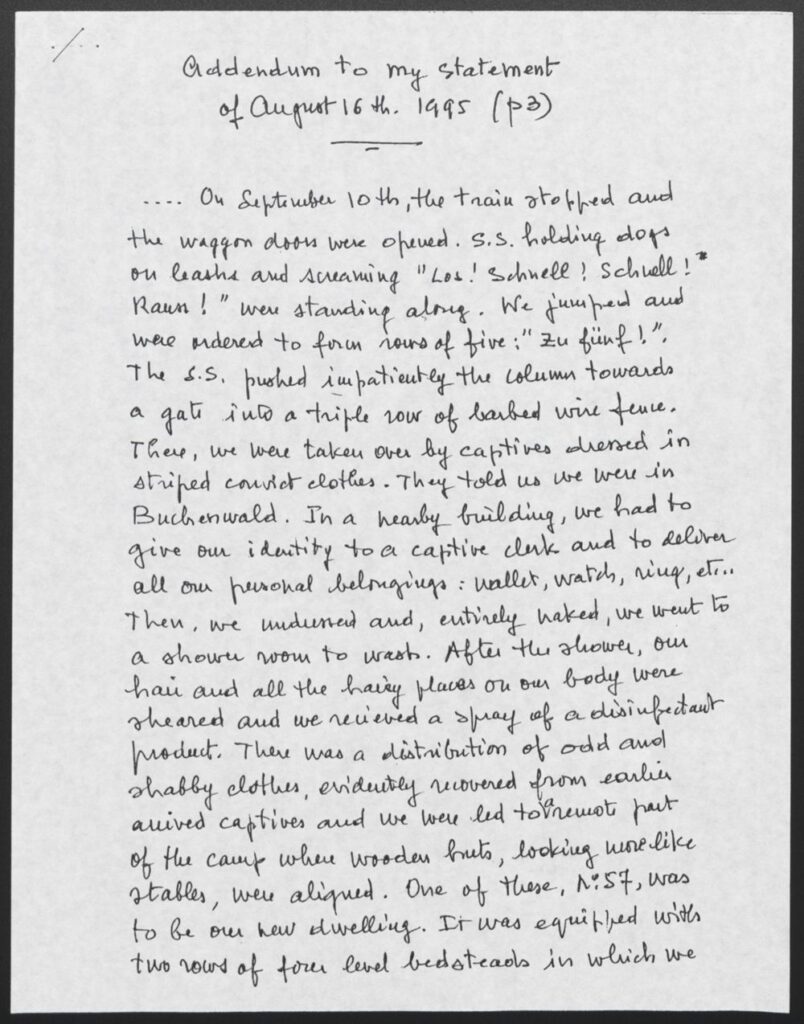

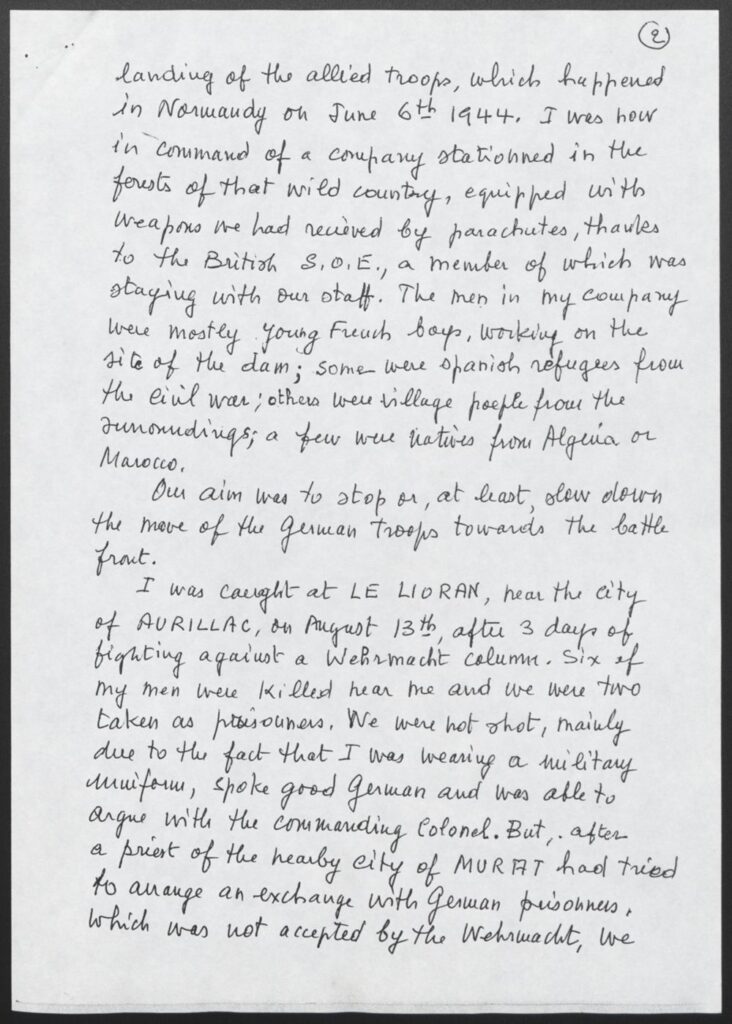

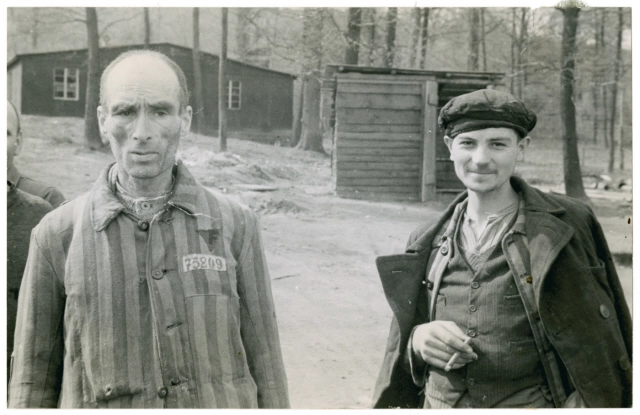

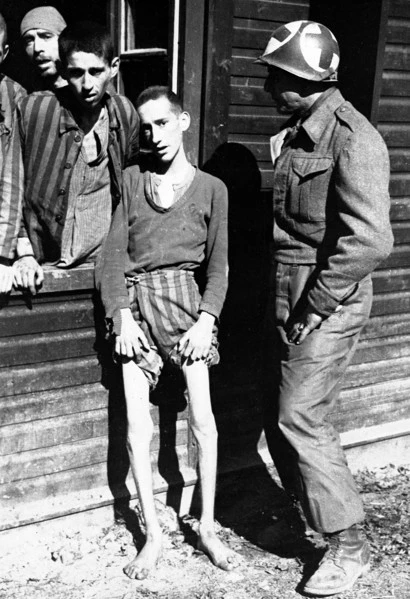

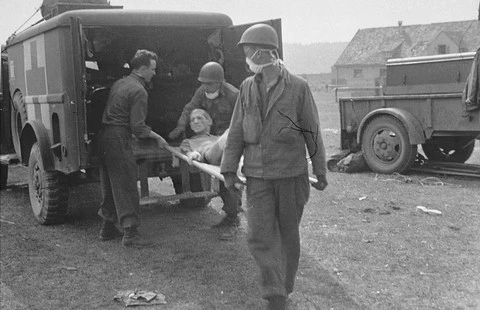

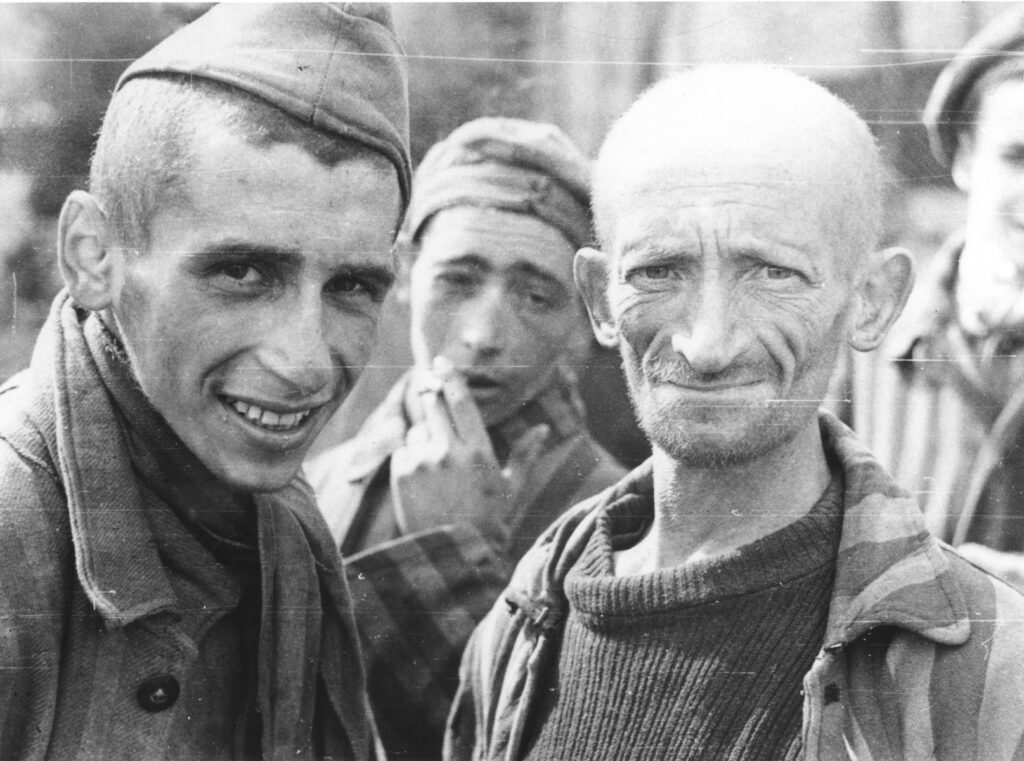

The camp was filthy, crawling with lice an inch long, Metrick said. The first thing the soldiers did was strip off all the prisoners’ clothes and burn them, he said. Then they gave the emaciated survivors a little food. The prisoners thought the soldiers were cruel for giving them so little to eat, Parent said. They didn’t understand that they could have died if they had gorged themselves, Metric said.” [9]

“As we descended from the ambulance, they kissed our shoes. We lifted them to their feet. These walking skeletons were young men, looking aged. They told us we were the first Allied personnel they had seen.Some were covered with lice. Their faces were drawn, pale and gray. Most of the living huddled in their huts on cots, too weak to stand. From a tree swung the corpses of two inmates, hanged just days before. No one had had the energy to climb the tree and cut them down.

Until the guards had fled two days earlier, they had been working at their job 12 hours a day, digging what was to become an underground factory in the Harz Mountains for Messerschmitt fighter planes and V-2 rockets. The Nazis had selected the slave laborers from the large concentration camps. They had calculated the economy of slave labor as dispassionately as a packing house calculates how to get the most out of a pig.They gave the men rudimentary housing, just enough food to keep them working and no medical attention. Thus they had the benefit of their labor for about a year at a cost of a few pfennig a day, until the men died of exhaustion or disease.

Martin Adends, from Amsterdam, age 55, guided us about the camp. He had been captain of a Dutch freighter. When the Nazis overran Holland he joined the underground and participated in acts of resistance and sabotage. He was caught distributing an underground newspaper and ultimately sent to this camp.

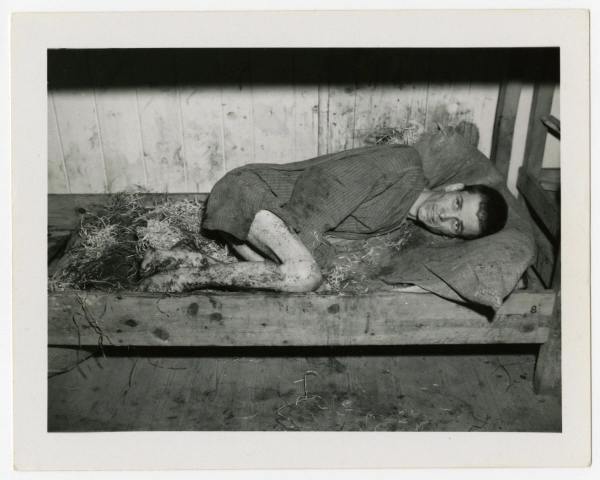

Many survivors were barely alive. They showed us a large pit, one of several, covered with earth and lime, containing, they said, about 350 bodies of those who had died during the course of their labors. We were told that most had died of weakness and disease, but that about 50 had been hanged as disciplinary examples.”[11]

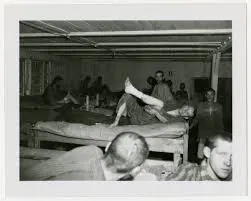

“When we approached the camp, the shock of seeing walking skeletons was overpowering. When the War Crimes Commission General and his staff and I entered one of the barracks, the horrible smell of decaying bodies and the stench of fecal material took an unbearable choke-hold on us. As we looked around at the walls they were all covered with feces. The sick inmates suffering from dysentery were too weak to go to the latrine so they just backed up against the walls and relieved themselves.

As we walked along at the wooden bunk beds and his photographer taking pictures, we saw the starved dead bodies and a sight that still haunts me. I saw one man moving and went to him. He was lying alongside a dead man I asked him if he understands English and with his eyes bulging out of hollow openings in a deathlike skull he said yes. His body was crawling with giant ugly lice. I asked him how long he has been lying next to this dead man. He said he died two days ago. When I asked him why he did not get out of bed he said he did not have the strength to get up out of bed. I kept staring at the enormous size of the lice crawling all over him it was an awful sight.

It was at the visit that I took this past April that I found out from the survivors of the camp that the Nazi Guards had fled three days before our Division came. They left everybody without food or water. They ordered the remaining three thousand prisoners who could still walk to line up in 6 groups of five hundred and took them on a death march while warning anybody hiding will be shot by the soldiers that are coming later.

As we left the barracks we passed a prisoner without legs, blind and terribly beaten who asked who we were. When we told him we are the Americans he said” I know I am not going to live much longer but thank God you finally have come. As we left the camp I’ll never forget the Generals remark as he turned to me and said” I would never believe it if I had not seen it with my own eyes.” And this was one month before the war ended.

It took me almost two days to get rid of the lice that were on me because of that visit. I had to boil my clothes in a large oilcan and used DDT to powder my body before I got rid of them.” [18]

The commandant of Langenstein-Zweiberg — according to the testimony of Kenneth Zierler — was bludgeoned to death at the hands of his former victims not long after the liberation:

“That afternoon a six-foot German, ramrod straight, dark, knickered and hosed, a Heidelberg scar on his cheek, strode into the courtyard of the manor house. The two Polish survivors were visibly agitated. They kept pointing at the visitor who, in English, demanded to see our commanding officer. He claimed that our soldiers were going into the village of Langenstein, stealing eggs and chickens. Somebody escorted him into the manor house to the colonel.

Our Polish survivors asserted that the visitor was commandant of the concentration camp, the man immediately responsible for the deaths of those whose bodies we saw in the lime pit, responsible for the two dead men we saw hanging from the tree, responsible for the miserable cruel existence of the walking skeletons I had seen in the camp. He must be arrested, they said.

I relayed the accusation to our commanding officer. The visitor denied the charge. Our commanding officer said that he could not pursue the matter, that there was no machinery by which he could detain an apparent German civilian. I returned to the courtyard, reported the decision. The Polish survivors looked at me in disbelief. Their outrage was contagious, and by now needed no translation. Our soldiers gathered around them, nodding in agreement.

In a little while the German strode out of the manor house and began to cross the courtyard. The two Polish survivors moved to the side of the mess truck where tools were carried. One pulled the shovel from its holder; the other the pickax. They stood in the middle of the courtyard, facing the man they identified as the concentration-camp commandant. By now there were some 30 or so soldiers in the courtyard. I was the only officer. The soldiers barred the exit and formed a circle around the alleged SS commandant. The Polish men began to swing their bludgeons. The German, who apparently had not sensed what was going on, was surprised, put up his arms to fend off the blows. He did not scream. He tried to run, but there was nowhere to go. The shovel and the pickax struck him again and again as fast as the semi-starved survivors could swing them. They caught his legs, and he went down.

I thought to myself, ”I am being party to a barbaric act and putting myself in the position of the Nazis. Everyone is entitled to a fair trial. Am I not obligated by the code of civilization that I respect to step in and stop this?” But I did nothing. I don’t know that I could have stopped the frenzy. I told myself that, in excuse. From some hidden reservoir of energy the young Poles struck the fallen body again and again and again. They split his skull. He moaned but he did not die. They swung and swung until they could swing no more. But he did not die. Utterly exhausted, the Poles could no longer lift their tools. They let the shovel and the pickax drop to the ground and fell to their knees, panting for breath. There was a moment of silence emphasizing uncertainty. But only a moment. Then a sergeant swung the carbine from his shoulder and put a bullet through the head of the hapless alleged SS commandant.” [11]

What it Meant to be Liberated

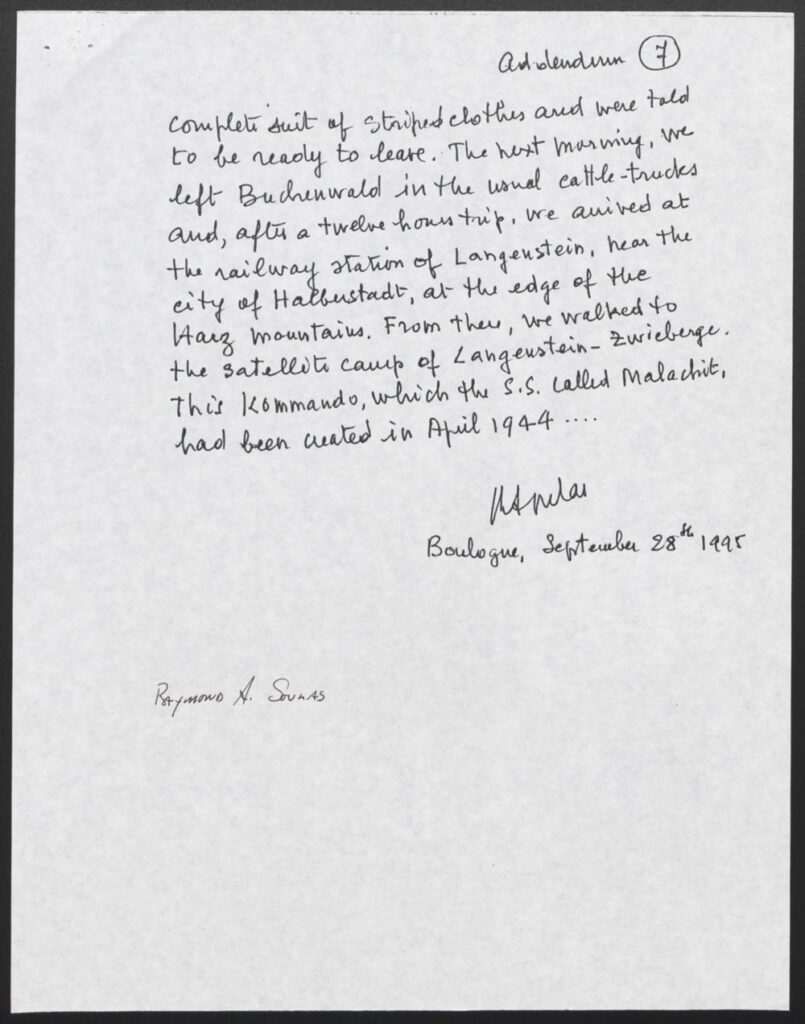

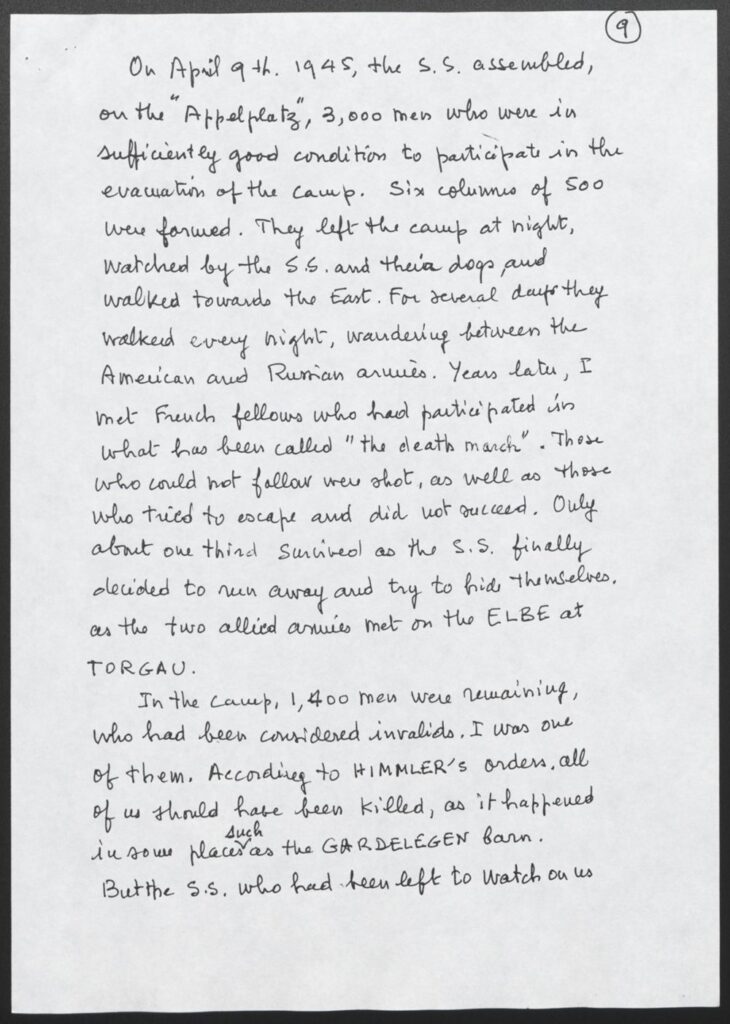

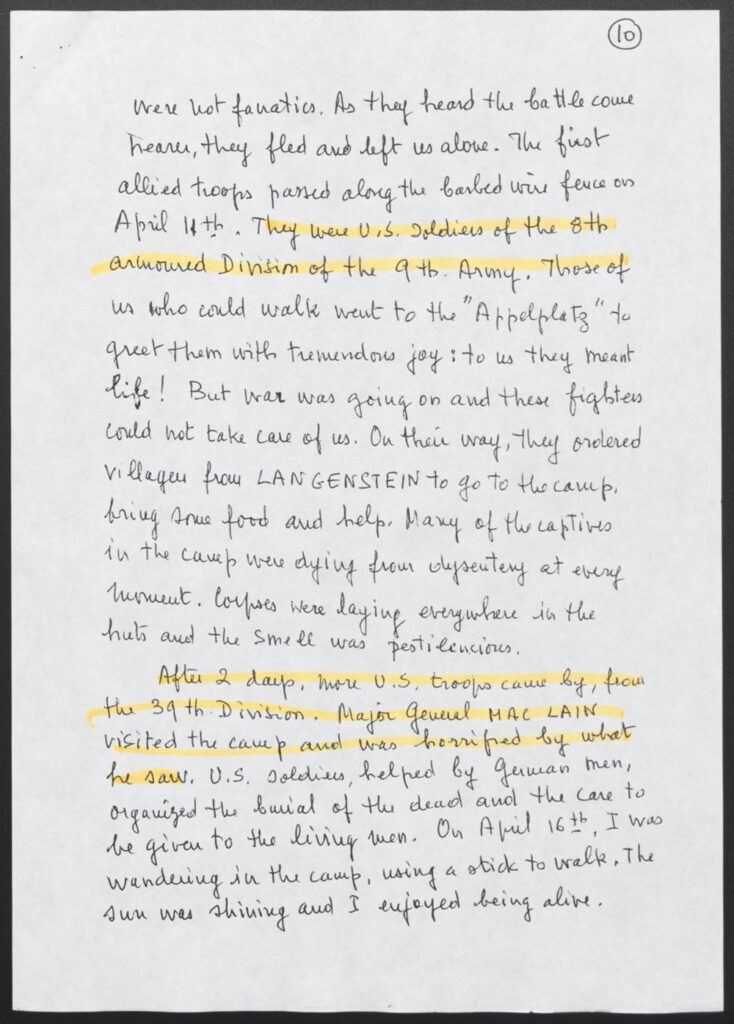

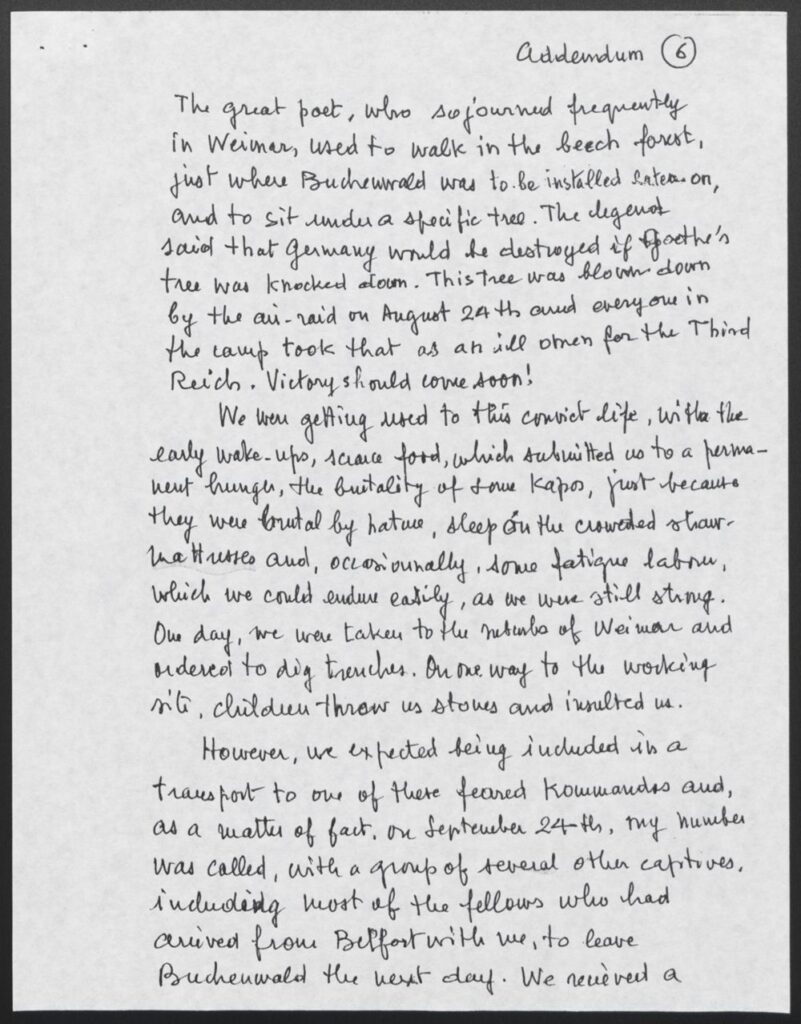

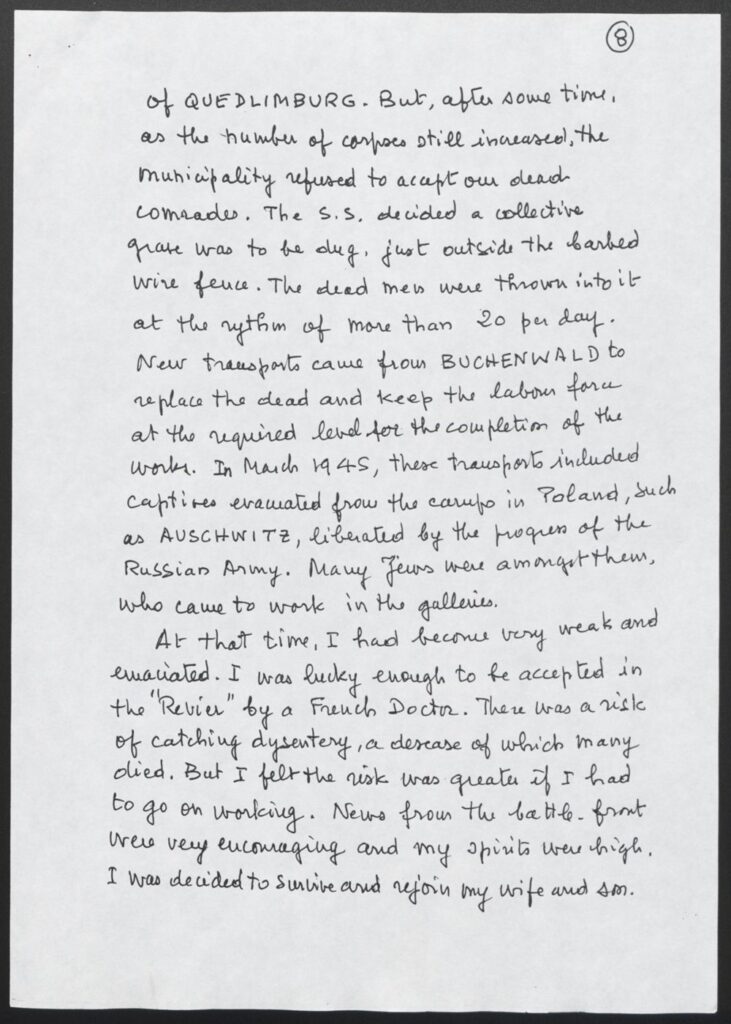

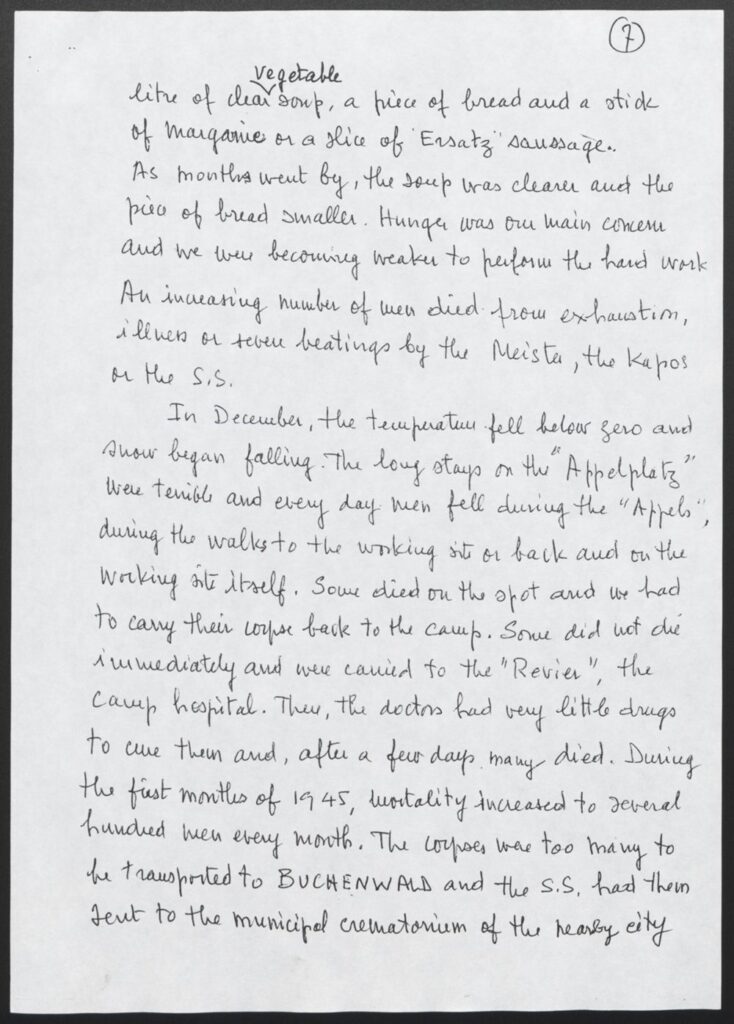

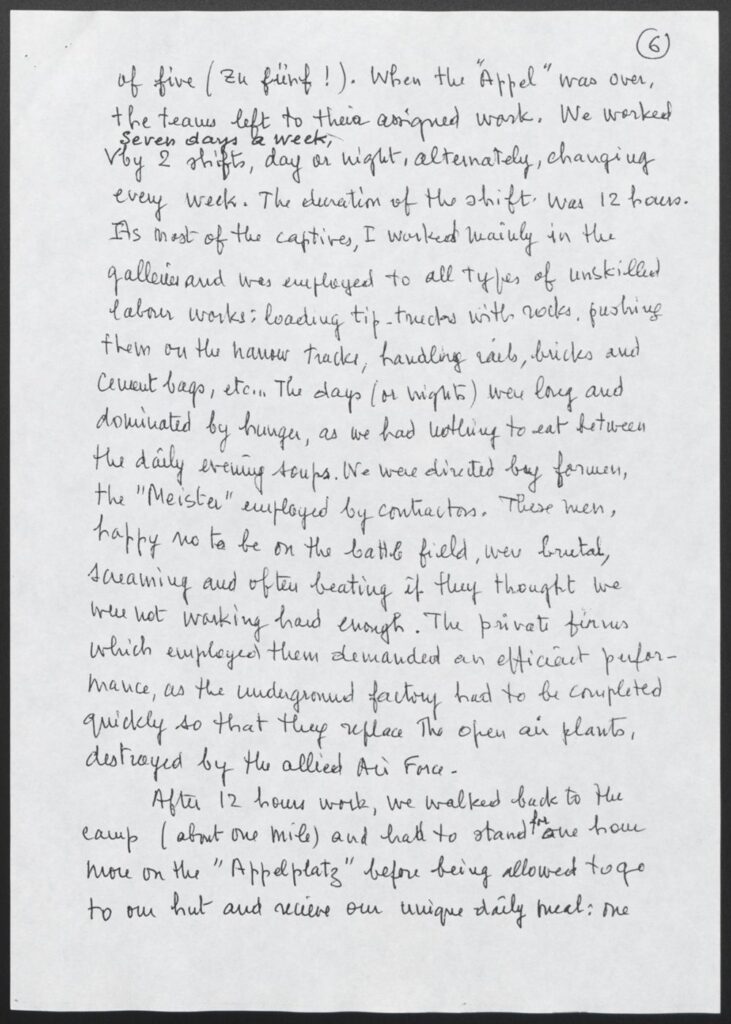

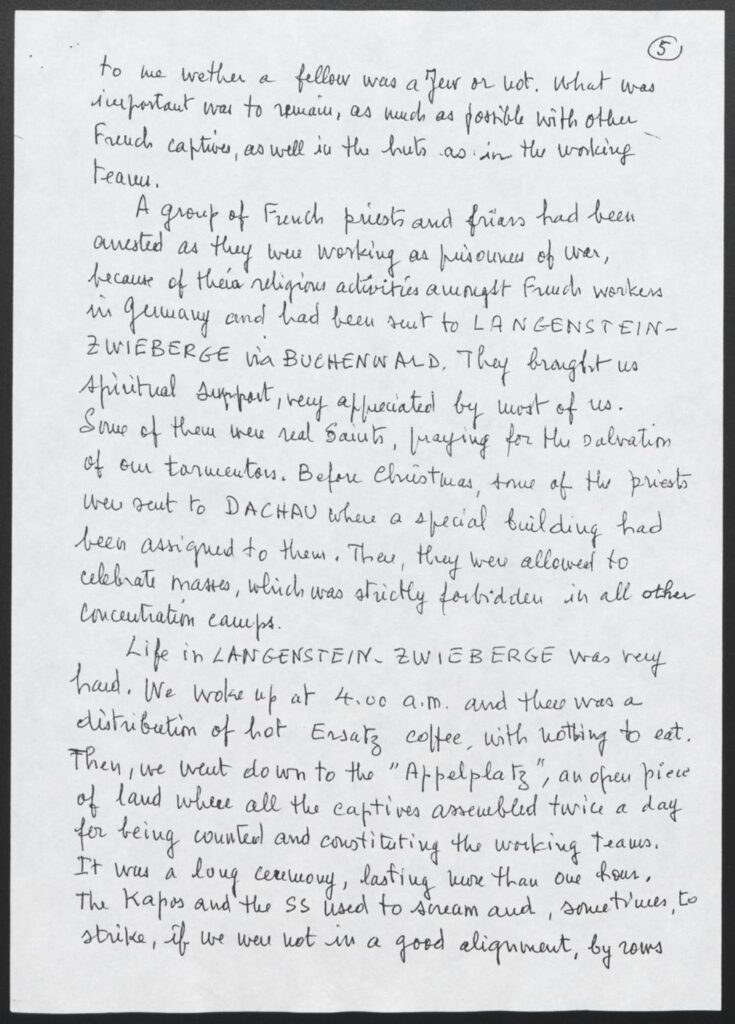

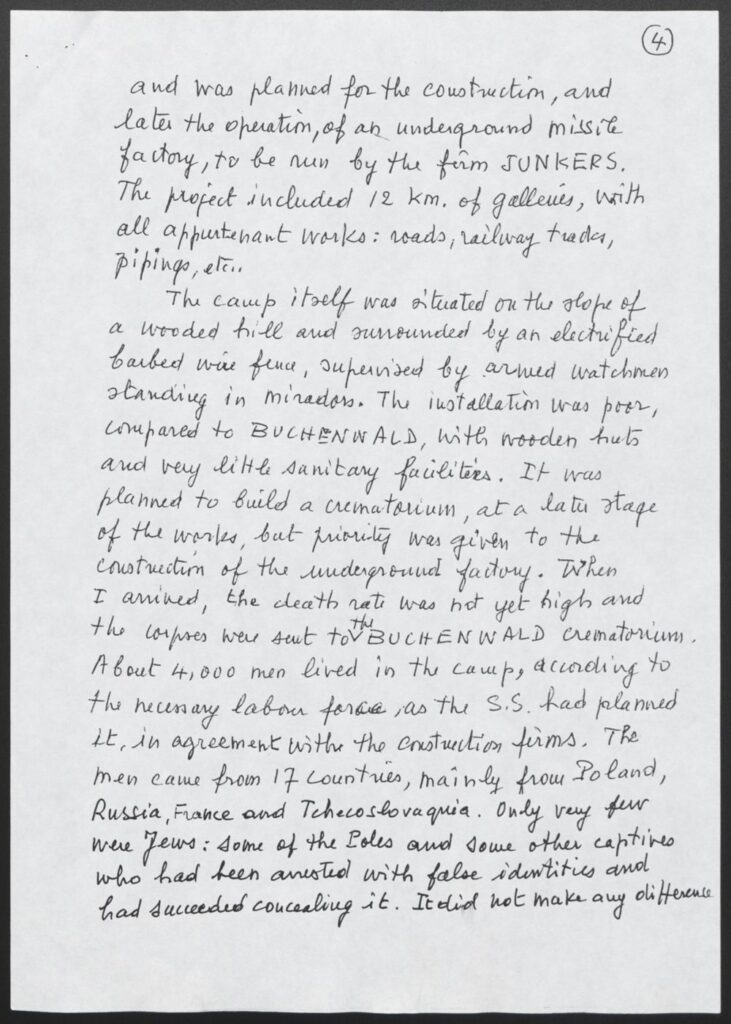

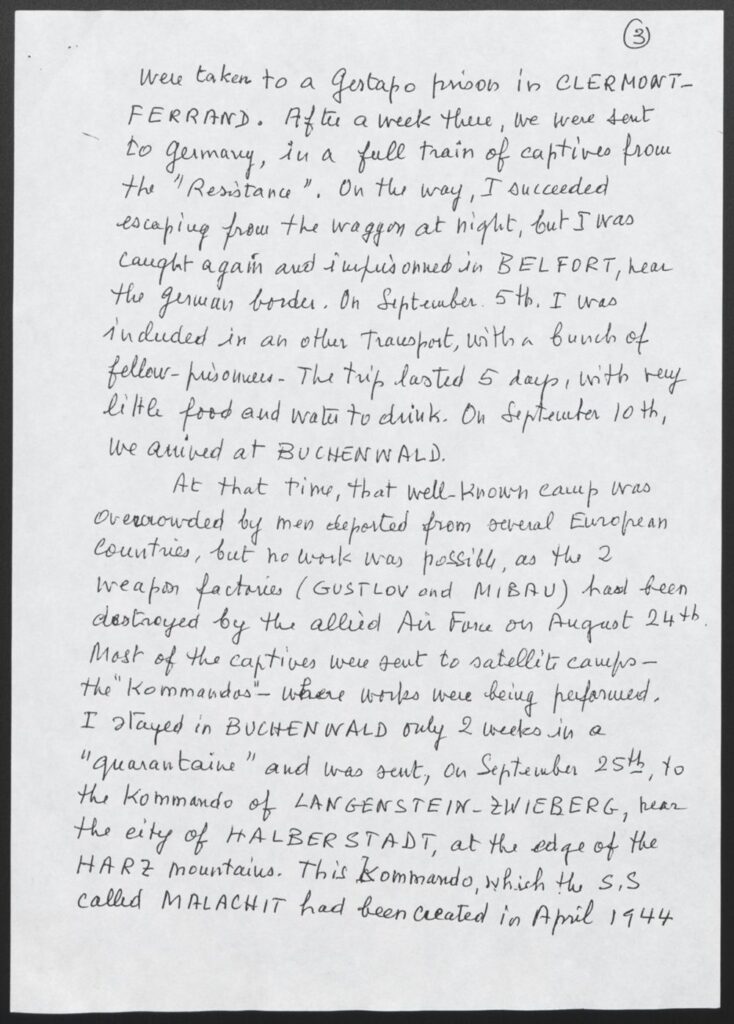

Raymond Soulas was among the survivors of Langenstein-Zweiberg, and his account is one of the most moving things I’ve ever read:

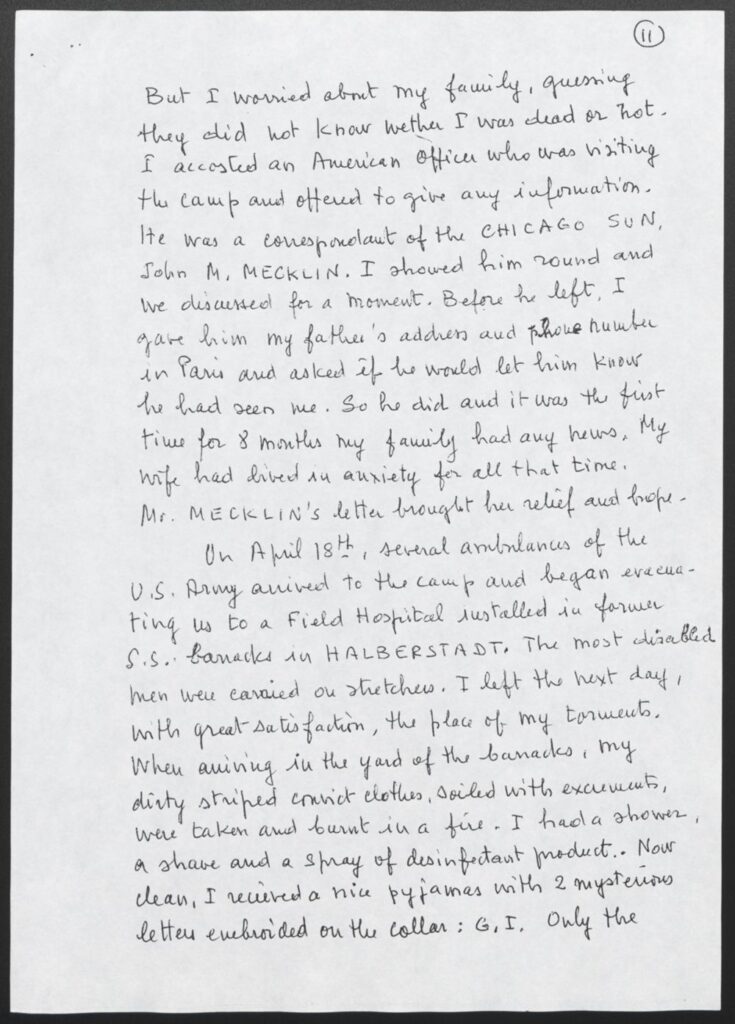

“I accosted an American officer who was visiting the camp and offered to give my information. He was a correspondent of the Chicago Sun, John M. Mecklin. I showed him round and we discussed for a moment. Before he left, I gave him my father’s address and phone number in Paris and asked if he would let him know he had seen me. So he did and it was the first time in eight months that my family had any news. My wife had lived in anxiety for all of that time. Mr. Mecklin’s letter brought her relief and hope.

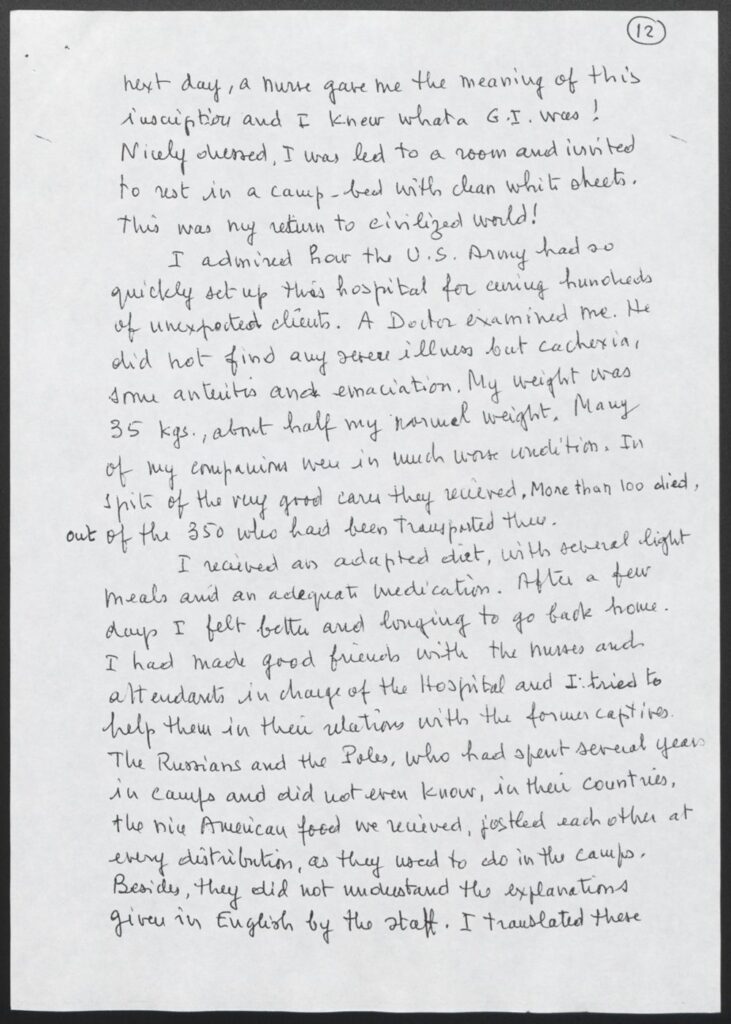

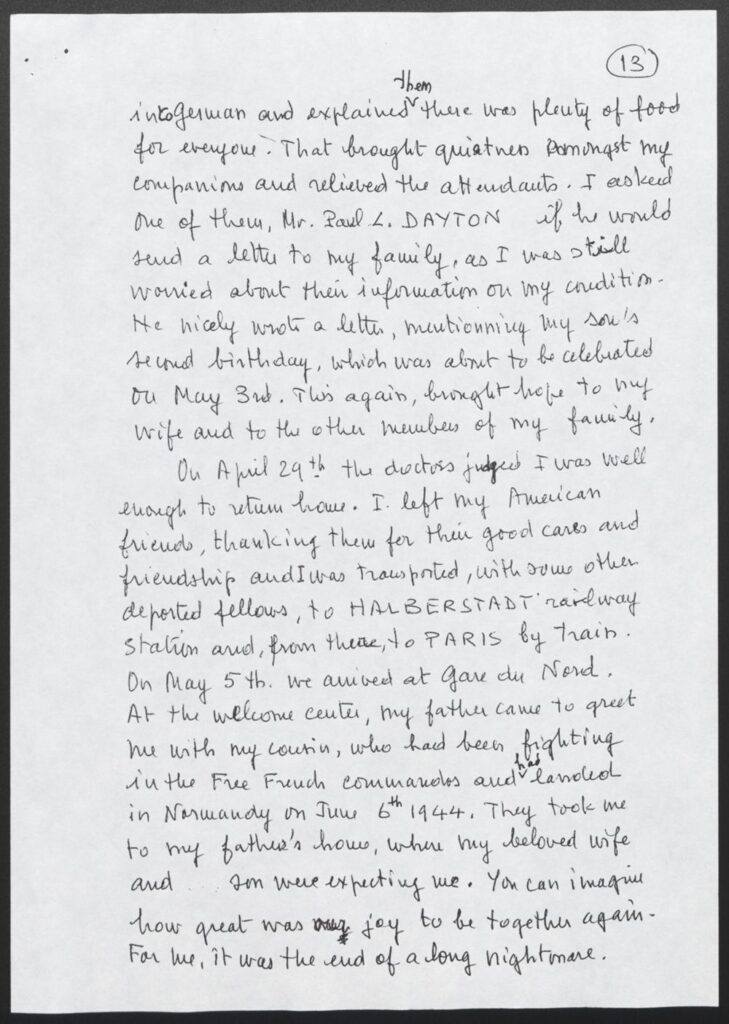

On April 18th, several ambulances of the U.S. Army arrived to the camp and began evacuating us to a field hospital installed [within] the former S.S. barracks in Halberstadt. The most disabled men where carried on stretchers. I left the next day, with great satisfaction, the place of my tormentors…I received a nice [pair of] pajamas with two mysterious letters embroidered on the collar: G.I. Only the next day, a nurse gave me the meaning of this inscription and I knew what a G.I. was! Nicely dressed, I was led to a room and invited to rest in a camp bed with clean white sheets. This was my return to the civilized world!

I asked one of them, Mr. Paul L. Dayton, if he would send a letter to my family, as I was still worried about their information on my condition. He nicely wrote a letter, mentioning my son’s second birthday, which was about to celebrated on May 3rd. This again, brought hope to my wife and to the other members of my family.

On April 29th, the doctors judged I was well enough to return home. I left my American friends, thanking them for their good cares and friendship. I was transported, with some other deported fellows, to Halberstadt railway station, and from there, to Paris by train. On May 5th, we arrived at gau du Nord.

At the welcome center, my father came to greet me with my cousin, who had been fighting in the Free French Commandos and had landed in Normandy on June 6th, 1944. They took me to my father’s house, where my beloved wife and my son were expecting me. You can imagine how great was joy to be together again. For me, it was the end of a long nightmare.”[20]

Combat in the Dying Days

When people think about the Wehrmacht, they often picture the elite and hardened soldiers who swept through Europe with incredible efficiency. Without question, the 8th Armored encountered plenty of these battle-tested units (17th Panzer Division was especially tested and definitely encountered the 8th), but they also fought against some of quasi-civilian military resistance. They encountered some Hitler Youth contingents and some scattered members of ‘Werewolf” — a military guerilla movement assembled from German citizen and commanded by SS commandants.

This reality adds an entirely new dimension to his experience in the war — imagine the gut-wrenching uncertainty, spending each moment wondering if you’ll have to face elite soldiers who have years of experience and success on the battlefield, or combatants who have no business fighting at all. The ‘Werewolf’ units had little to no organizational structure or success on the battlefield, but the 8th Armored was among the first to encounter any Werewolf units. Combine this reality with the myriad of other unspeakable jobs the men of the 8th Armored had to perform — cleaning up destroyed tanks and vehicles, handling the remains of their own friends and fellow countrymen — and the unspeakable nature of their duties become difficult to comprehend.

Not for nothing, the 8th Armored had joined the war incredibly late in the game. By the time the division had entered France in January of 1945, the Soviets had already liberated Warsaw, the Germans had officially lost The Battle of the Bulge, and the Red Army — by the end of the month — had advanced to within 50 miles of Berlin. By February 3rd, 1945, large scale bombing raids on Berlin had already begun. Japan would be another monster to slay, but Germany was by all accounts on borrowed time.

I think it’s safe to assume that at the forefront of everyone’s mind, especially the men who served in the 8th Armored, was the desire to not be the last man killed. Who wants to die in the waning moments of a war? The Russians had already broken the back of the Nazi war machine in Stalingrad, and all parties knew it was a matter of when, not if, the Germans would finally surrender. The only lingering doubts seemed to exist in the quality and duration of any remaining resistance within Germany itself. Allied generals worried about Hitler cloistering himself away in one of his many mountain villas with fanatically dedicated SS units. Guerrilla warfare would be particularly brutal, even more so in the treacherous terrain of the Bavarian countryside.

In the Western world, there is a misconception of war as being manly or tough. It isn’t. Men are cut down in the prime years of their lives, innocent people are killed in the crossfire, and those that survive often are stricken with permanent ailments. This is why I have an infinite level of respect and admiration for what my grandfather did — not because he was Rambo, but because he made a lifelong sacrifice that was unspeakably painful. He witnessed the purest evil while defeating fascism in Europe. All to preserve the free society that I enjoy today. What he — and the rest of the “greatest generation” did was selfless in ways that we should never fail to appreciate.

My grandfather spent two or three weeks in or around the Harz Mountains before he and the rest of the 8th headed to Czechoslovakia for parades, light patrolling, vehicle maintenance, and some well-deserved booze and demobilization.

“Our major job in the area proved to be manning road blocks in the strip of land bordering on the Russian-held section of Czechoslovakia and guarding a large PW Camp which contained close to 10,000 German prisoners. Despite the language handicap, we got along on good terms with the Czechs and found (sic) enough to drink without having to resort to the Russian drink of beer spiked with gasoline. No sooner had we settled down to this routine of duty, plus the usual half day training schedule, than the Army began its Redeployment Plan and the 8th Armored Division was slated for. (sic) demobilization.”

Melvin ‘Bud’ Allen died on April Fool’s Day in 1996. I only have three memories of him — cowering under the barbers chair after he took me to get a haircut, driving with him when he stopped at drive-through liquor store (and I got a lollipop!), and lastly, laughing after he popped out his dentures to scare my sisters. I can’t say I ever knew him, I can only say that I wish I had. Christopher Hitchens expressed much of what I feel about my grandfather in his piece about his own father, Commander Eric Ernst Hitchens.

“The Commander, who had seen action on his ship HMS Jamaica in almost every maritime theater from the Mediterranean to the Pacific, had had an especially arduous and bitter time, escorting convoys to Russia “over the hump” of Scandinavia to Murmansk and Archangel at a time when the Nazis controlled much of the coast and the air, and on the day after Christmas 1943 (“Boxing Day” as the English call it) proudly participating as the Jamaica pressed home for the kill and fired torpedoes through the hull of one of Hitler’s most dangerous warships, the Scharnhorst. Sending a Nazi convoy raider to the bottom is a better day’s work than any I have ever done, and every year on the anniversary the Commander would allow himself one extra tot of Christmas cheer, or possibly two, which nobody begrudged him. ” [Slate]

The same mixture of admiration, respect, jealously and frustration flows through me — how could I possibly do anything better with my own life? The Second World War had its share of ethical dilemmas, but at its core, it was clash of good against evil in the simplest of terms. There was right, and there was wrong, and that for once, good actually prevailed over evil. The world rose up and fought fascism together. Millions of people sacrificed for children they would never know, and for free societies they would never live to enjoy. There’s something in that selfless action that all of us can learn from, can aspire to, can use to make ourselves better in every way.

Melvin Allen — and the entire 8th Armored Division wouldn’t be formally recognized as liberators of the Langenstein-Zweiberg concentration camp until 1995, but what was responsible for the 50 year delay?

Project Malchit (Komplexlanger-12)

After World War II ended, Halberstadt fell under East German control, and the Nationale Volksarmee created Komplexlanger-12, codenamed ‘Project Malachit’ a massive communications center and munitions depot chiseled into the former Halberstadt-Zweiberg camp tunnels. Leaked diplomatic cables from 1973 indicate that the Americans believed the East Germans were using KL-12 as tank storage in preparation for a war with the West.

“AS EXAMPLES OF THE ALLEGED 2,000 TANKS IN ADDITIONAL ACTIVE SOVIET UNITS IN THE NGA, THE DEFENSE MINISTRY REPS CITED THREE TANK REGI- MENTS IN THE GDR–RESPECTIVELY LOCATED AT GLACHAU, HALBERSTADT AND QEDLINBURG–EACH OF WHICH ACCORDING TO FRG INTELLIGENCE POSSESSES 100 TANKS” [3]

As early as ’73, the United States and, by extension, NATO, believed Halberstadt had some tactical value to the East Germans and were actively monitoring the site. They were right to worry — as these videos from urban explorers and other enthusiasts show a fully operational military hub, complete with telecommunications equipment, air purification systems, diesel generators, loading docks, and barracks. This might explain why Washington felt the need to stay quiet about any details about Halberstadt-Zweiberg, but the existence of a military base doesn’t seem very titillating (or, for that matter, seem all that necessary to keep the liberation of a Nazi concentration camp secret.) [14] [15]

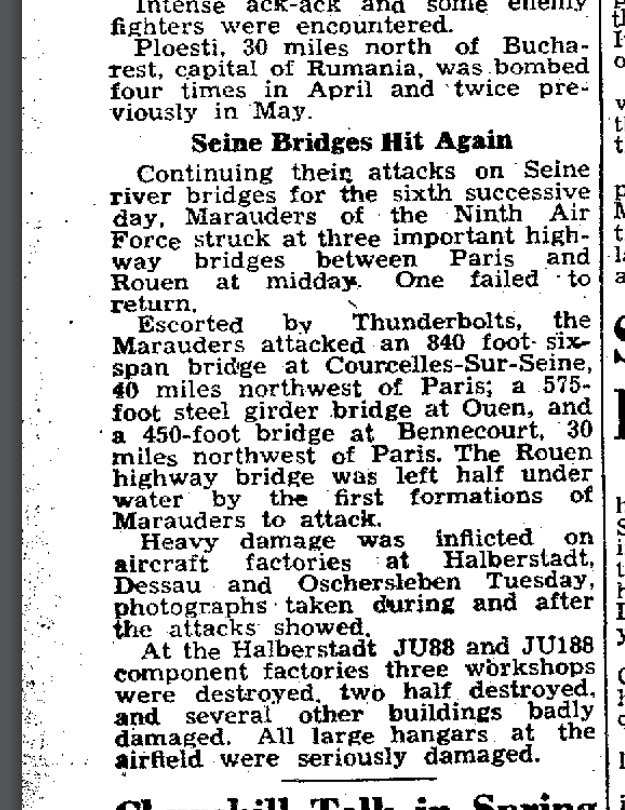

Initially, I believed that the Americans kept quiet on Halberstadt because they had discovered some secret Junkers technology used for the German V-1 and V-2 rockets, but this is probably untrue. Halberstadt-Zweiberg was never an active factory for Junkers, and production for any V-1 or V-2 rockets never began there in the first place. Der Spiegel maintains that Malachit “nie ein einziges Flugzeugteil produziert werden würde” — never produced a single aircraft component.

At best, the Allies might have learned how Junkers factories were designed, but little else, and wouldn’t have much need to classify that data. I think it’s much more likely that the US Army saw Halberstadt-Zweiberg as a ‘smaller’ type of concentration camp, and simply didn’t see it as a priority until Dr. Metrick officially brought the matter to their attention. During the war, the 8th had seized top secret caches of German intelligence, but not anywhere near Halberstadt:

Captain Thomas Q. Donaldson, Division G-2 Section, discovered a valuable store of top secret German documents which had been dumped in an abandoned water-filled mine shaft at Reverhausen. These documents contained results of tests and experiments on airplanes, propelled missiles, submarines, and rockets. After four days of work by an engineer squad from Company B, 53rd AEB, all documents were recovered by air to Paris. Alert troops of CCA discovered important documents of the Political Culture Section, Office of Foreign Ministry, near Eland. These had previously been considered of such vast importance by the Nazis that two divisions had been risked to keep them from falling into Allied hands. A staff officer from Headquarters, 9th Army, declared them to be worth “a far greater expenditure of manpower.”

The delay in recognizing the 8th Armored as liberators is still puzzling. I was able to find an article written in “The Stars and Stripes” in 1945 that specifically names the 8th as liberators, so I don’t believe it was seriously classified by the U.S government. Some FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) requests by other researchers have revealed a small amount of aerial photography that was taken of Halberstadt. If I had to speculate, I would imagine that the methods and equipment used to collect that reconnaissance (perhaps first on the Germans, then, later, the Soviets) was very classified and KL-12 was simply swept up in that classification. It was a low-capacity camp, and compared to many of the other extermination sites, was considerably smaller. It seems unlikely that the camps at Halberstadt contained many secrets worth hiding.

The German government used KL-12 up until 1995, and by one account, the Soviets demolished some of the complex that was dug by victims of the Holocaust. By another, the NVA simply built this facility directly on top of the 60,000 square feet dug out by prisoners of Langenstein-Zweiberg. KL-12 existed for a while in a state of historical purgatory — the German government and the local residents are aware of its historical value, but fear opening the entire complex to the public for a wide array of issues.

“The complex is now owned by a local resident. He wants to open the site as a place of interest (i.e. ex NVA installation) but has met with stiff local resistance. The local authorities have effectively prevented him from opening the site publicly, or using it as an exhibition centre as he wishes to do. He is taking them to court now in an attempt to reverse their decision restricting his planned use of his bunker. The issue seems to be one of just how the bunker complex is ‘remembered’ and/or perceived. The WW2 use of the place still ’embarrasses’ perhaps, but definitely holds sway over the GDR use, so it would seem. There are various issues, but I understand that the confused local worry is that if opened publicly, the fear is that it could be homed in upon as a sort of shrine for neo-nazis as it is felt (by the local community) that the Jewish and other KL victims should be remembered there. There is definitely conflict over this, and – as I understand it – the issue is rather how should the inmates and the concentration camps be remembered.” [2]

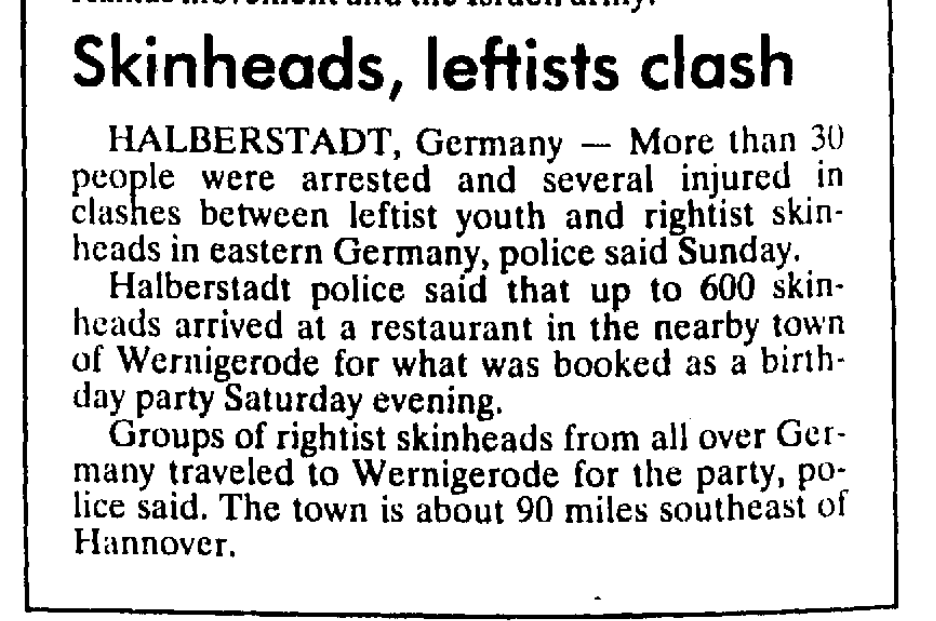

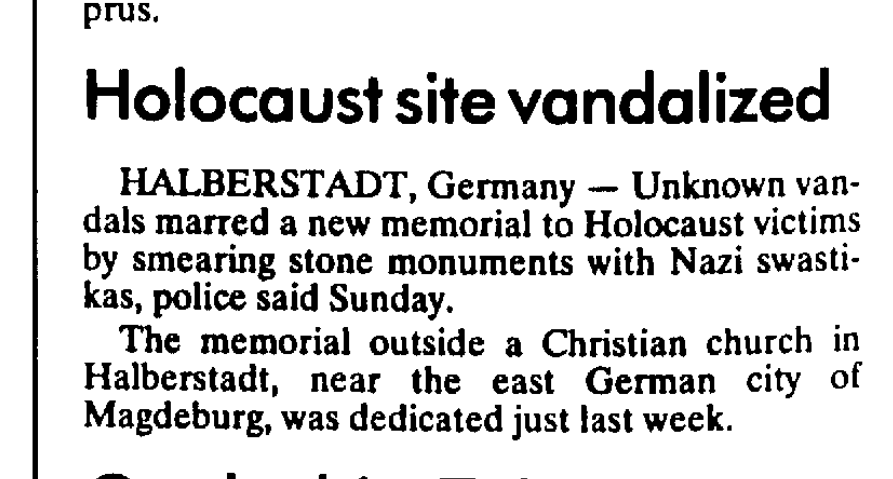

It’s a conflict that is familiar to many Germans, and their fears about neo-nazi pilgrimage are sadly not unfounded. The memorial site at Langenstein-Zweiberg was crudely vandalized in 2006, swastikas were carved into parts of the memorial structure, and two information sheets were ripped off. In the same year, two men illegally dumped 5,000 pounds of garbage into the tunnels of KL-12. The regional government — as well as the local population — have good reason to be concerned about the future of the memorial site. It is undoubtedly difficult to manage a facility nearly nine miles in length, structurally unsound in many places, and, by the way, still could store chemical weapons.

Citations

[1]http://www.spiegel.de/einestages/vergessene-orte-a-946505.html

[2] http://www.bunkertours.co.uk/germany_2003.htm

[3] https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/1973BONN16014_b.html

[4] http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10006149

[5] http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/wwii/articles/usarmyczechopoverview.aspx%5B/embed%5D

[6] http://www.8th-armored.org/books/leach/tw02.htm

[7]http://www.8th-armored.org/books/36th-hist/36h-ix.htm

[8] http://www.8th-armored.org/rosters/8-sstar-80.htm#12-styp

[9] http://articles.sun-sentinel.com/2004-01-22/news/0401220153_1_camp-prisoners-lice

[12] http://www.jpost.com/Jewish-World/Jewish-News/Germany-Concentration-camp-memorial-vandalized

[13] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bAeZxE5Sok

[14] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ROcsguTGh_4

[15] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7hOGaGWiAi8

[16] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MdVUQcHSw_8

[17] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTyU9Z2RCso

[18] http://www.8th-armored.org/books/78b_metrick-2.htm

[19] https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-8th-armored-division

[20] https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn504753

[21]https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1000794

[22]https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn503183

[23]https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn677765

[24]https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn503509

[25]https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn508471

Other Notes:

- If you want to get in contact with me in regards to this article, email me at adam[at]limadrive.com

- Versions of this article have appeared on a couple different domains I own – it has been revised at least three times, so in the interest of version control I will call this revision (4/16/25) v4.

- I would love to write a book on this topic but I just had a baby and time is quite limited. I have briefly pitched it to publishers, none of whom were interested in underwriting additional work.

- There are materials and artifacts in the holds of the Library of Congress and some related artifacts within the USHMM’s repositories as well. As time permits I would love to visit both and piece more of the story together.

- Others have reached out to me for access to information I have compiled during research. For a limited version of these materials, see the ‘repository’ below:

Repository