Rome – Part I

In the inaugural games in the Colosseum, the historian Cassius Dio claims over nine thousand animals were killed for sport. That is such an oddly specific number and it sticks in my brain like a thumbtack.

The structure itself was likely financed with the sacking of Jerusalem around 67 AD. Josephus tells us that more than a million civilians were killed and a little under one hundred thousand people were enslaved. The Romans would lose ten thousand fighting men in the battle, and Judea would lose two or three times that.

One of the seven wonders of the world is born from this brutality. The amphitheater is a monument to death worship, to enslavement, to excess, to greed, to warmongering. It is horrible. It is enchanting. I do my best to admire the engineering and architecture instead of being captivated by the violence.

But from the darkest gloom, beauty can still grow. The familiar vexation of the human condition rings true in the Colosseum, perhaps more clearly here than anywhere else on the planet. No emperor reigns forever, no evil escapes sunlight indefinitely. Hope springs eternal. Humanity does what it must and creates goodness. Where the suffering increased, the beauty increased all the more.

What starts in Rome as monuments to individual narcissism, with time, ends up as invaluable shrines to the skill of the humans who designed them. Humans have always suffered under despots. This condition is not new, and is unlikely to ever change, to our despair. But each wall built by ego eventually is reclaimed by the earth, each cathedral to arrogance collapses under its own unsustainable weight.

Our guide leads us over a jagged mosaic of stone, far from level, but the rocks are smooth like pebbles plucked from a river. This floor, he says, is original. We step on work completed just seventy years after the crucifixion.

Our Airbnb host leaves a book for us on the coffee table. Rome in 3D. Its pages pop out and fold over one another, revealing intricate illustrations of how the metropolis likely looked in antiquity.

Through this book, I first came to learn of Saint Telemachus. Legend has it the monk was martyred when he put his body between combatants in the stadium in an effort to end the bloodshed. Depending on which source you consult, Telemachus is either stoned to death by a crowd annoyed by the delay, or run through with a sword by a gladiator. The monk’s death, though, appears to represent an ethical and cultural pivot. Honorius is said to have banned gladiatorial fights soon after, and the last known fight takes place in 404.

One committed person can and does make a difference, and no amount of cynicism can prove otherwise.

People have been coming to Italy for holiday since the 17th century, and the Faustian bargain of a tourist economy has persisted here ever since. One in five Italians is employed by tourism, and the revenue generated by it represents 5% of all Italian GDP.

The service industry here, however, does not suffer fools, and does not throw itself on the sword of eternal customer rightness. Your order might come, it might not come at all, or you might get something extra because they like your smile.

An economist might tell you that this is the very nature of supply and demand – that there is insatiable demand for a limited supply of service industry workers, and those who remain can be a bit choosier about who they serve as a result. As the world wrestles with straining supply chains and rising inflation, this is likely the direction the whole planet will soon take.

In the United States, folks will hand you a receipt, or your change directly. In Italy, nearly every cash register has a bit of concave glass or plastic that functions as a receptacle for change, ostensibly designed to minimize skin-to-skin contact. I wonder if this has always been the case, or if this has newly emerged following the nation’s harrowing skirmish with Covid-19.

At the time of writing, more than 166,000 Italians are dead from the Coronavirus. They were among the first to enter lock down, and the quarantine measures enacted were among the most stringent in the world.

I see another American wandering the grounds of the Coliseum; the text on his shirt reads “The only vaccine I need is beer.”

I understand why the rest of the world thinks we are all that stupid.

On the first morning, we are served espresso and upon the first taste, are surprised with its overwhelming sweetness. Our barista has preemptively added a packet of sugar, presuming these Americans will dislike the drink as it is traditionally prepared.

I’m not offended by this, in fact, I’m certain her impulse has been molded by thousands of prior American tourists pantomiming disgust when what they receive does not taste like their regular Starbucks order.

But sugar is actually quite nice, and the barista is confused when we order a second.

During any international travel, I am especially keen to see what American influences take hold in the host country. I like to learn what words need no translation between us. My guide in Belize knows of Saint Louis and Missouri when I mention it because those words are printed on the labels of Budweiser products.

“Bud Ice!” he exclaims, head tilting backwards, syllables dragging for emphasis, his mind revisiting a beloved memory. “We drank it at clubs because it was hard to get on the island. We thought it was fancy and we loved it.”

In Italy, I see clear evidence of America’s soft cultural power. They have statues of Superman. I hear Italian language versions of Lizzo’s high-energy pop anthems. Cheeseburger joints outside bars give the kebab shops a real run for their money. I watch as Napoli toddlers nibble contentedly on KFC chicken nuggets.

I first learn of another gruesome school shooting while channel surfing on Italian cable. Those words needed no translation either. 15 nino muerto. Killer 18 anno. AR-15. Our national shame, our grotesque firearm obsession, our never-ending dark parade of children to the morgue is our lasting international legacy. It outweighs all others.

It is breaking news in Rome, same as Chicago, same as Cairo, same as anywhere when kids end up dead for no goddamn good reason.

Part II – Vatican City

There are pup tents for the homeless within fifty meters of the Basilica. These are mostly visible at night. They sleep rough within a stone’s throw from the Vatican Bank, a repository of wealth so lavish it would make Scrooge McDuck blush. God’s treasury is very secretive, but experts think it is probably worth about $5.6 billion.

A litany of pontiffs and martyrs lie here in state. It is a mausoleum, primarily. The bones of Peter himself are supposed to be buried somewhere underneath the church. Each gravemarker overflows with magnificent art, sculptures, paintings, statues, each produced by artisans who have brought a lifetime of talent to bear on their productions. The humans interred here rest in an unusual splendor, typically reserved for kings. It is, truly, a wonder of the world, and its beauty defies all description.

I have studied enough history to know there are wicked and righteous pontiffs. And nearly every person, evil or not, deserves a dignified resting place when the time finally comes. I am not entirely filled with hatred when I visit, just mostly filled with hatred. I despise this place, entering the city first at night, drunk, spitting mad, praying I could see the meteor strike in person that would level it.

But the Catholic Church can have their golden inlays and oceans of marble. It is, as said previously, a triumph of architecture and art, a crowning achievement of the entire species. It is missing one thing, though. A memorial for all of the lives they have ruined, for all of the children that were raped under their care, for each and every suicide they have directly caused, for all of the incalculable pain and suffering they have unleashed upon this world. They are wolves in shepherd’s clothing; destroying the weakest and most innocent members of the flock their God charged them to protect.

We need another Samson to push on these pillars and see them destroyed. It is only in their dust that humanity can heal.

I push on the pillars as I pass and they do not budge.

In the years I spent at Bible college, I learned the interpretation of scripture requires patience and curiosity. I was taught it is an acquired skill, and one that takes years to properly build. As a budding theologian begins to sculpt that exegetical muscle, a habit of caution should emerge, I was told. Not from fear, but humility. Who am I to say, really, who Jesus was, or what he thought?

That is all fine and proper, but there is only one type of person Jesus curses at. There is only one type of person the perfect savior mocks. And it is not the prostitute, not the tax collector, not the adulterer, not the glutton, not even the Roman occupier, but the money changer and the rich.

If I had one wish, I would transport Jesus of Nazareth to this palace of greed, to this altar of decadence, so he could see how these twisted Pharisees have responded to his call of poverty with private jets and Swiss bank accounts. His father’s house is now a den of pedophile vipers.

But that viper den is, in equal measure, one of the most beautiful places on earth. As an adult, you learn to accept contradiction as commonplace. After the idealism of your youth evaporates, you begin to realize there are problems that will never change, not in your lifetime, anyway. Thousands of years from now, humanity will gaze upon the Holy See and wonder how we could tolerate it for so long.

Not for nothing, the problems that vex the Catholics would be incredibly simple to fix. They can sell off a sixteenth of the wealth amassed in their coffers and use the funds to execute a real truth and reconciliation commission. They can permanently excommunicate any members who have abused children. With those funds, they could create a global network of trauma counselors who could help prevent the damage from compounding further. And to stop future outbreaks of pedophilia, the church could allow its priests to marry, recognizing these men and women are humans, and require healthy sexual outlets.

Nothing is stopping the Vatican from inviting an impartial third party to carry out an independent investigation of all of their sexual abuses. This could be enacted immediately. They are not powerless to untangle their web of corruption. Those in positions of power simply awake each morning and choose not to. Child predators have never had a greater friend in all of human history than the Vatican.

It is this reality that so powerfully colors my perspective. I cannot see the statues of priests clutching toddlers without wincing. I am unable to disconnect the magnificent beauty of the troves of artwork without seeing the pain that shapes its shadows.

Vatican City continues to enjoy an outsized influence over the Italian populace. The Catholic Church does no real investigation of pedophile priests in this country; those who are caught are often reassigned and the cycle of abuse begins anew.

Survivor networks in Italy are often forced to handle the investigations instead. One such network, Rete l’Abuso, has tracked 350 cases of pedophile priests in the absence of real police work. One could only imagine the mental toll it must take to process the trauma of such vile assaults and then take up your own detective work. It is a repugnant insult to add to their unspeakable injuries.

In modern times, we have begun to quantify the price of these abuses. 33% of women who have been raped contemplate suicide. 13% of those will attempt it. Now zoom out, and try to imagine just how many people, over the entire course of human history, have been abused by this organization. Their pain is inconceivable.

It is often said the Vatican thinks in centuries, not decades, and their global grip on cultural and religious power has hardly slipped, even as religious affiliation, in almost every country, steadily declines. There are old churches on every corner. We slip into one right as service begins. Young girls in lilly-white confirmation dresses listen dutifully to their priest.

In 2017, Infant Annihilator, a death metal trio from the United Kingdom, was suddenly banned from Spotify and Apple Music. They are a niche act in a very niche genre, and it would not be unkind to say their appeal is quite limited. Their lyrics are indeed repulsive, but their primary muse is the Catholic Churches’ brazen and continued rape of children.

The streaming services would, under pressure, walk back this oddly selective act of censorship three days later. One does not need to wonder who was behind the “complaints” both companies cited when criticized for their brainless censorship of art; the same organization that employs abusers, relocates them when they are caught, and cuts checks to make their victims stay quiet is the only party that could truly be responsible. There is no opponent too small attack, no dissent too minor to quell.

As we queue to enter the Basilica’s Dome, I am passed by an Australian woman who apologizes, explaining that she is not jumping the line but has been told by security she must buy a cardigan from the Vatican’s gift shop that covers her shoulders. God did create her shoulders, but I suppose the Lord did not want to see them on that day.

The man behind me is wearing shorts and an AC-DC shirt. His outfit is not scrutinized for its modesty. Neither are my stained Pumas and Volcom shorts I should have tossed a year ago, pockets barely held together by re-stitched seams.

Part III – The Food

The food is divine everywhere. We spend big on Veritas, one of twenty restaurants in Naples that have earned a Michelin star. Deep fried squid balls coated in a crunchy rind of sesame seeds arrive with the first course. It is a master’s class of texture and temperature. Wine, mostly white, is paired with courses of tuna, scallops, and shrimp.

The finest of all these dishes comes in the middle of the service. Poached egg, agretti (sometimes referred to as ‘saltwort’), fava beans, shaved asparagus, with pecorino cheese and crisped culatello. It was perhaps the finest meal in all my life. I depart from the table with an emperor’s guilty buzz.

On that topic, there are a great many things in my life I feel guilty for, and older Adam would have a few choice words for younger Adam if given the opportunity. One such regret revolves around the college education I largely squandered. Greco-Roman history bored me as a teenager, and having seen the ruins of this empire first-hand, I wish I drank less and studied more.

No one is more puzzled by this than me. That era of history has all of the things that should pique the interest of any young man; depraved sex, unrelenting violence, political intrigue, speedball economics, and a bunch more crazy sex.

But the empire that catches my attention on this trip is Ferraro, the Italian confectioner that produces Nutella. It is served on virtually everything. I enter a café and I can see five buckets of it atop a bar the size of paint cans. Twenty five percent of all the hazelnuts on earth are used for the beloved spread. I welcome these sweet overlords.

The quality of the food on offer will decline the closer one gets to the primary tourist draws. I do not begrudge the operators of these establishments for this; they meet a need and nothing I saw was served in contempt or in an unsafe condition.

As the vacation goes on, individual ingredients, rather than entire dishes, increasingly begin to capture my attention. Tomatoes taste sweeter, citrus sharper, basil smoother, mozzarella creamier. I opt for a Napoli pizza on one evening, it comes with arugula, basil, oregano, prosciutto, and it all comes topped with what I can only describe as the most perfect cherry tomatoes.

In the States, I cannot buy even organic cherry tomatoes that do not have a bit of musky funk to them in the middle. Maybe it’s all imaginary – psychosomatic brain impulses telling my tongue these tomatoes – maybe even sourced from the same place I always get them from somehow taste better – but I have never had better. They are fresh, watery, salty, clean, bright and sweet.

Yes, you must eat your fill of salted meats and the mozzarella the Campania region is best known for, but do not neglect the vegetables. They are delightful. On a whim, I eat a flatbread sandwich from a butcher’s shop that contains only red cabbage and blue cheese. Equal parts punchy and crunchy. It is the perfect light, but flavorful lunch, especially when paired with a tart white wine.

Wine is remarkably cheap, sometimes as cheap as €3-4 a glass, and in this country, the pours are mighty goddamned generous. I drink to excess on perhaps four nights out of seven but awake each morning with no hangover. If beer is more your style, in Naples, I bought a liter of Peroni for a couple of Euros. Believe me when I tell you that heaven for good alcoholics must look quite a lot like this country.

As the parents drink under restaurant umbrellas, children chase soccer balls across slippery cobblestone, and no one seems to mind the noise. After two drinks, I don’t notice it either.

The Italians do not, in my limited observation, have much interest in scolding their young into silence during meals. A table next to ours is celebrating a birthday dinner for an adult, and they do not expend much effort suppressing their youthful energy. No one partakes in the western ritual of the ‘kids table’ wherein the children are cloistered together and much cruelty goes unnoticed by guardians. By contrast, their tables are lively, diverse, and populated with people from many age groups.

In Salerno, we discover a cozy dive bar that sits catty corner to local park. There is a quaint library inside, tucked behind a set of stairs. I order a bourbon. Two elderly gentlemen try their English out on me as I belly up, but not before holding firm eye contact and proffering a gentle buona sera. I am moved by the decorum and etiquette. I wish I was less jet-lagged, more talkative. I am not surprised when I see the same two men in the same place the following evening.

Much ink has been spilled over the ethics of short-term rental sites like Airbnb. Setting that thorny issue momentarily aside, should you find yourself in the country, a kitchenette is preferable.

You will eventually tire of imposing on wait staff and will desire something simple and moderately home cooked. Don’t resist the urge. Street markets are plentiful, and it takes little effort (and money) to toss together a simple pasta dish with perfectly ripened vegetables and tinned tomato sauces for a fraction of what you’d pay to eat out. Pop asparagus or broccoli, buttered and salted into an oven for twenty minutes while your pasta boils (I spent less than €2 on a bag in a corner store.) We only make one meal at home in this fashion, and I wish we had done it much more by the time we leave.

Are there any lessons we can learn from Italy? Can I report on a robust EU economy chugging away during the greatest period of Euroscepticism? Can I whittle a stone of cooperative globalist hope away from the rising mountain of isolationism and brain-dead nationalism?

I used to ask enormous questions like these. And as a younger (read, dumber) idealist, I would write their answers with an unearned confidence. The problems of our planet have solutions, we need only to find them, I thought. Rightly or wrongly, I do not think this way, at least not anymore.

The mechanisms of human power take many forms. In time, progressives and revanchists alike get their turns on each of the levers. Increasingly, I am of the conviction that power never really changes hands at all. Where one force increases, another decreases in equal measure.

To move out from the abstract, the GOP has gained a legislative victory in their war of attrition against reproductive rights. What the left will gain from the loss is a widening grip on the soft power that surrounds the issue. As women are killed and maimed by this cruelty, the images of their butchery will fire across the globe as digital sparks. They will fuel the fires of change that are sure to come. The forces of cruelty will enter a period of exile and dormancy, and, in time, return to power again.

It is often said of occupational safety that rules codified there are written in blood. A similar idiom usually surfaces in conversations about military occupations and proxy wars. It must be your blood, your father’s blood, your sister’s blood that is spilled until the true cost of prestige and shared cultural values can be codified, then cast into iron and etched into marble.

The western world is teetering on a precipice of civil war, of political violence, of regressive and medieval brutality. Many of us shall not survive it.

But the wine here is very good.

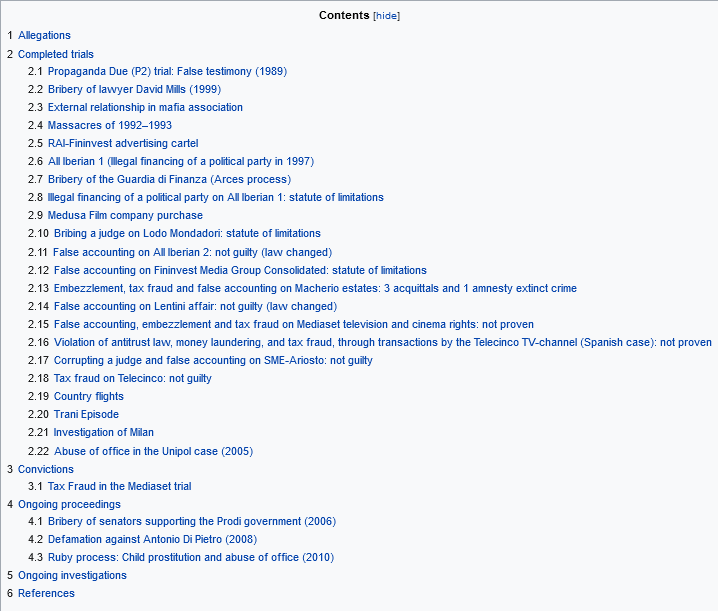

Italy has tangled with more than its fair share of corrupt politicians. The most clumsy among them, for my money, is Silvio Berlusconi. Here is a truly incredible table from Wikipedia that contains a list of his alleged crimes:

The best and brightest are taken from us too soon, or so the saying goes, and as Silvio’s eighty-five year old heart still manages to beat, one can take little umbrage with the idiom. Songbirds meet swift ends and cockroaches subsist. Americans and Italians should share a common political kinship, as they both understand how it feels when a single depraved leader turns the primary national export into shame.

The apex of that depravity arrives in 2013 when Berlusconi is convicted of sex trafficking:

Milan prosecutors on Wednesday requested former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi be jailed for six years for allegedly bribing witnesses in a 2013 underage prostitution case.

Berlusconi was originally found guilty of paying to have sex with El Mahroug, who at 17 was considered a minor by Italian law, and sentenced to seven years in jail.

Reuters

The Prime Minister leaned on every single lever of power at his disposal. He arranged to have the police detain the 17-year-old, concocting an invented diplomatic crisis in a sloppy attempt to conceal his disgusting behavior:

After a couple of hours, while she was being questioned, Berlusconi, who was at the time in Paris, called the head of the police in Milan and pressured for her release, claiming the girl was the niece of then-Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and that in order to avoid a diplomatic crisis, she was to be brought to the custody of Nicole Minetti. Following repeated telephone calls by Berlusconi to the police authorities, El Mahroug was eventually released and entrusted to Minetti’s care.

Like Weinstein, Silvo attempted to ‘catch and kill’ this story, and he was willing to pay €850,000 for the privilege. We know the details of this criminal transaction because, unbeknownst to the Prime Minister, he had been lawfully wiretapped right before he called to negotiate. While Berlusconi was hammering out the details of his bribe, he complains in the surreal wiretap audio that while he ordered eleven prostitutes for the evening, he was only able to fully consummate the transaction with eight of them.

The pattern displayed here will be familiar to Americans. A head of state guilty of a litany of crimes who, with the aid of no shame or dignity, will be comfortable shrugging off repulsive acts, and the worst people in the nation will shrug along with him. Even after his conviction, Berlusconi was able to convince the Supreme Court to reverse his lifetime ban from politics. It’s a dirty game everywhere it’s played, and the dirtiest usually win the most.

Part IV – The Pain

Dad died in January.

Every day since has been difficult. On many mornings, I do not want to get out of bed. A mental fog descended after his funeral and has not left. I somehow manage not to get fired from work. I don’t think I regain my smile until I step off the plane in Naples. And even that smile feels selfish and strange. I am depressed in one of the most beautiful places on earth.

In February, I stop drinking entirely. Partially because my doctor tells me lower my cholesterol, but mostly because I find the affects of alcohol are counterproductive to the grieving process. Him and I were estranged at the end, and things were complex between us, as things often are between fathers and sons. Booze became a distraction, and I hurt as much drunk as I did sober.

Life stops for a few weeks and I have nothing but the loss to think about, it dominates nearly all of my conversations, consumes all of my mental energy.

I felt guilty for having the money needed to buy this airfare, for having the ability to take time off work, but this trip has been in the making for a decade. My partner and I had Rome as a bucket list destination, and we were counting down the individual days gleefully. Friends tell us we’ve earned it. I have never felt such a disjointed mix of sorrow and excitement. I have never been in so much pain, and I have never been so fantastically happy. Life remains strange.

I tell my therapist the trip is exactly what I needed, that I had to wash the taste of sorrow out of my mouth, that the vacation was the reward of ten hard years of work, that it was the celebration of a thirteen-year marriage. I say and think all of the right words but it all feels hollow.

I was not prepared to write the words that would be etched into his tombstone. I first visit his final resting place alone. I am relieved to see it is indeed peaceful. There are imprints of deer hooves pressed into the freshly-turned soil. In the stillness, I can hear the gentle current of the Mississippi. It is a fine spot, better than most others, in fact.

Tennis is the thing Dad liked best.

Even when he was in his fifties, I don’t think I ever really beat him on the court. I might have made him drop an occasional set or two, but he was always able to serve his way out of trouble. When he was feeling good, he could still fire off a 90 MPH serve. Beyond velocity, his second serve had serious bite. He was a master of spin. It was like trying to return an angry curve ball.

Often, he’d hit the first serve fast and long, and on the second service, he’d send me diving into the fence chasing the ball, its flight path darting from left to right like an ornery hornet. “I can curve it one direction in the air,” he told me once with a smirk, “then spin it the opposite direction off the bounce.”

Bill wasn’t a tall man, but at the net, you wouldn’t know it. His favorite shot was the backhand smash, and it contained everything he loved about the sport. That stroke is highly technical, it requires precision to the millimeter, and it demands years of faithful practice to truly master. Believe me when I tell you he had mastered the backhand smash.

I would hit him high lobs when he’d approach the net just to avoid the shot. This did not meaningfully alter the outcome of the point; he’d snag those with ease, and make such a difficult strike look completely effortless. It was poetic, a real joy to watch. I have never been able to emulate it, and will forever remain jealous.

On the court, he was different person. Patient, measured, relaxed, precise. I like to believe that humans can instinctively recognize talents in others that take lifetimes to perfect. That there is an unmistakable efficiency of movement, that finesse and elegance are universal languages, no matter what the arena, no matter what the skill. He devoted so much of his life to tennis, and it showed. I was always eager to get my friends on the court with him, hoping they could get a glimpse of what I often saw when it was just me and him on the asphalt. Sometimes, he’d play with a wooden racquet just for the challenge, he said, but I suspected it was nostalgia.

I am five thousand miles from home and the image of an old wooden racquet still follows me.

Charlotte Cooper was one of the greatest to ever play the game. Her record of eight-consecutive Wimbledon singles finals would stand for eighty-seven years. Navratilova wouldn’t reach her ninth Wimbledon final until 1990, a feat that would require eighteen grueling years on the tour to break. Cooper won her first singles title in 1895, battling back in both sets down 0-5, winning the tournament with literally no margin left for error. In a losing effort against Muriel Robb in the 1902 finals, Charlotte Cooper would set another record for the longest women’s final, scrapping through an unprecedented fifty-three games. She goes on to win her fifth and final Wimbledon championship in 1908 as a mother of two.

A couple weeks before we leave, I find myself in possession of more than four thousand feet of racquet string. When I was in high school, we’d run a sporting goods store together, and this represented the last of its inventory. I find a local tennis charity that provides equipment to children who can’t afford to play the game. I hope that would have made him smile.

I pass Vesuvius again, this time while on the train from Rome to Naples. The summit fills the aperture of the cabin window.

It is faith that moves mountains. Faith the size of a mustard seed is all that is needed. With enough of it, I can conquer all challenges. These are the Judeo-Christian mores I am raised with, and I take them, with sincerity, to Bible college as a teenager, with the intent of joining the ministry.

But by the time my college years end, I have no faith left, not even an iota remains. I tell Dad of this reality and he is furious, indignant, scathing. It is the truest test of our relationship.

Even in the heat of that conversation, at the apex of his disappointment and anger, he insists on being thorough on one last point; that he still loves me, and that he always will. It has since become the most cherished memory of my entire life.

And in this way, Dad prepared me completely for anything that comes my way. Love must come first, must remain unconditional, and everything else is details.

Part V – The Rules

In my limited international travel, I have started to see the wisdom in three statements:

Doing the Big Thing

You might be saying to yourself as you prepare – why should I do the big thing?

Everyone else has already done the big thing, and I am special and different! Furthermore,

you might feel an urge to avoid the big thing because you aren’t the sort of low-rent tourist

that falls easily into the traps the locals set for you.

It’s the volume of people, you think, that will keep you away from the big thing, and the big thing will just be more trouble than it is really worth.

I don’t make a habit of telling folks what to do, but this instinct is one that should

be ignored. Effiel Tower? Yes. Mona Lisa? Macu Picu? Yes.

Go do the big thing because it is big for a reason, and you are small, and upon seeing it,

you will find the well of your humanity refreshed and renewed.

Doing the Cliché Thing

Yes, when you are overwhelmed and awake at odd hours thousands of miles from home,

you should eat the McDonalds cheeseburger, and I am certain in that moment it will taste

magnificent. This is culturally universal advice, by the way, simply substitute ‘McDonalds’ for whatever creature comforts your people, whomever they are, God bless them, typically run to for a taste of home. On the last night in Italy, I spend €40 at McDonalds and I feel no shame, and neither should you.

The Brits like pubs, the Germans like acquiring beach towels and lying on them, and Americans need some of that fake beef and cheese. It will not make you less of a seasoned traveler, it will not make your experience inauthentic, it is merely an admission of your humanity.

Doing the New Thing

If your attitude is correct, and you have entered another nation, with its own language, customs, and culture with the proper respect and humility, you will not need the advice above.

The thing the locals do, the thing that you do not understand, that is the thing you must do. Your sinuses and tastebuds are still smoked from the high altitudes of your flight anyway, so try something different.

In Belize, the breakfast for almost everyone was a fryjack – egg, cheese, maybe some type of meat

jammed into a deep-fried pocket of bread. You want to eat that new thing, whatever it is,

trust me.