Part I – Actun-Tunichil-Muknal Cave

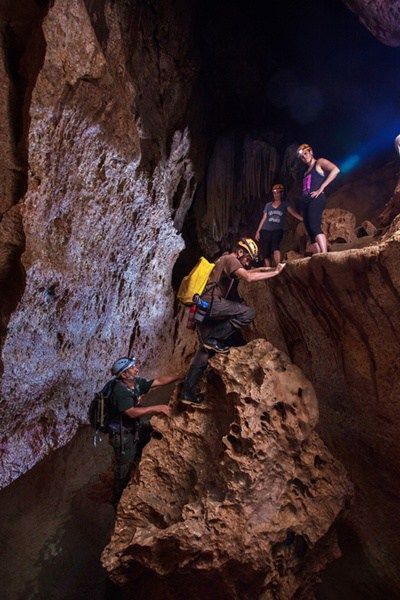

(These images are not mine, cameras are not permitted in the site.)

“The name Actun Tunichil Muknal translates as “Cave of the Crystal Sepulchre,” and the locals know it as “Xibalba” after the Mayan underworld. The Crystal Cave was traditionally believed to be an entrance to hell, a deep fissure in the earth filled with rivers of blood and scorpions.

Atlas Obscura

We stay at an Airbnb run by a family of British expats. They know we’re headed to ATM before we mention it. “Right, that’s the only reason most people come out this way.” A gluttonous iguana lounges atop a towering palm tree in the distance. The homeowner chuckles. “Lucky little devil, I’ve seen him up there with three females at once!”

I was not entirely aware of the immense danger this tour represented, until I found myself clambering up a twenty-foot ladder that was perched on slippery rock. The guides are exceptionally skilled, however, and have committed much of the site to memory, giving unique names to various features of the cave. One especially narrow bit spelunkers must squeeze through is affectionately dubbed ‘the decapitator.’ We are given precise instructions on handholds and where our feet should land first. The rock feels worn in these spots, eroded, like the dent your big toe leaves in the bed of your shoes. Eric the tour guide is jovial, cracking jokes throughout, doing his best to keep things light so no one freezes up. “You know why they call it ATM, right? Another tourist missing!”

We are told to proceed in socks as we approach some of the most archeologically significant elements of the cave. We are also instructed, quite firmly, to enter with reverence as this site is the spiritual home for the entire nation. Our path is outlined by bright pink flagging tape, the boundary sometimes mere inches from priceless artifacts and human remains. “You see, right there!” Eric the tour guide exclaims, his brows furrowed in genuine anger, pointing at a fracture running along one of the skulls. “Tourist leaned in with a camera and dropped it, broke it open.”

Eric uses his headlamp to illuminate the rising stalagmites, cathedral spires jutting upwards from frigid blue water, arresting in their intricate beauty. He tells us that the natural features of the cave, under torchlight, and from just the right angles, became a magical theater of shadow puppetry. There is evidence these stalagmites had even been modified – shaped to form the images of their gods so that their shadows would fill the walls of the cave like a moving picture. There are accounts of Maya royalty performing pilgrimages to ‘the Cathedral’ during famine and drought for ritualistic bloodletting.

The tour culminates with a final ascension into the Crystal Maiden’s burial chamber. The bones, calcified, sparkle like tinsel under our piercing flashlights. There is total dark and total quiet within the cave. It is restful, and many have come to rest here. I can say with absolute certainty that it was one of the best single things I’ve ever seen with my own eyes.

Part II– Xunantunich

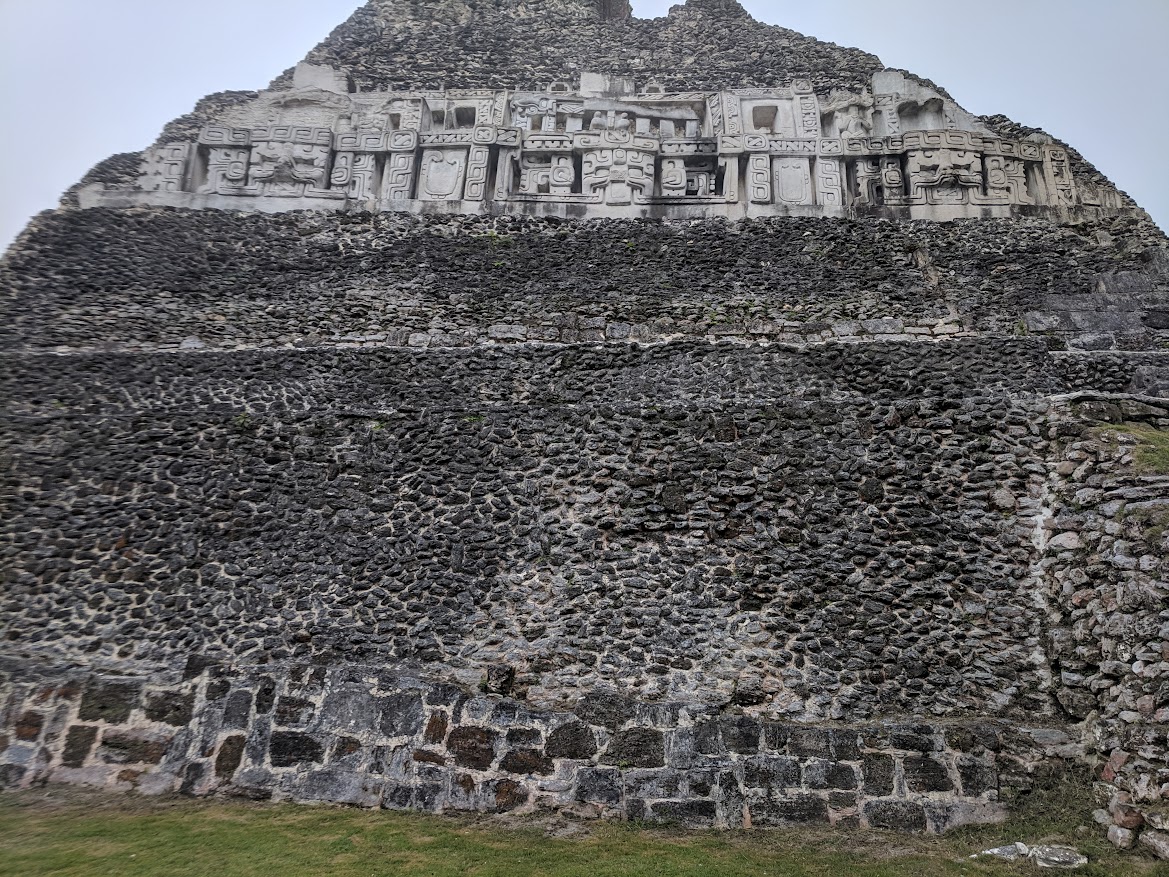

“Xunantunich emerged as a regional center during the Samal (A.D. 600—670) and Hats’ Chaak (A.D. 670—780) phases of the Late Classic period. Arguably, this rapid growth and florescence was initiated under the auspices of nearby Naranjo. Although the polity achieved political autonomy in the following Tsak’ phase of the Terminal Classic period, civic construction diminished and rural populations declined until the site collapsed sometime during the late ninth or early tenth century.” Cambridge University Press

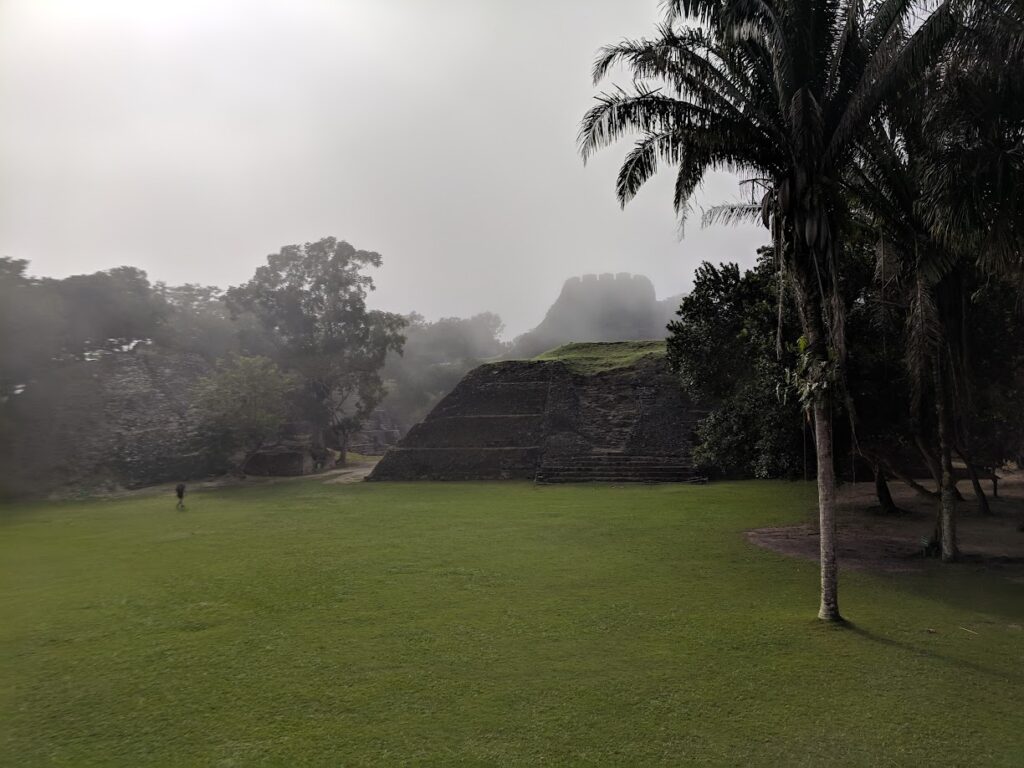

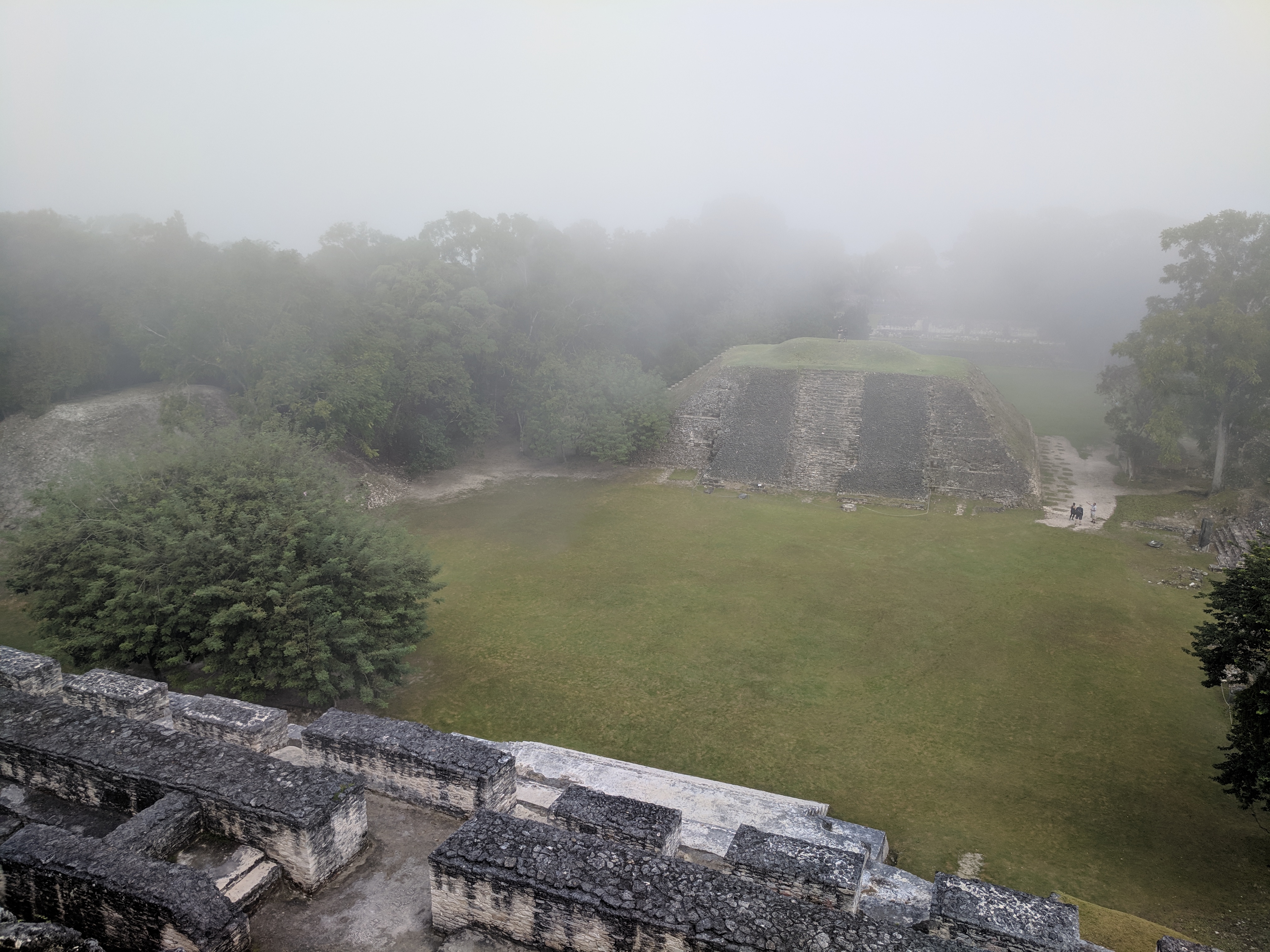

We arrive before the morning’s fog has a chance to dissolve.

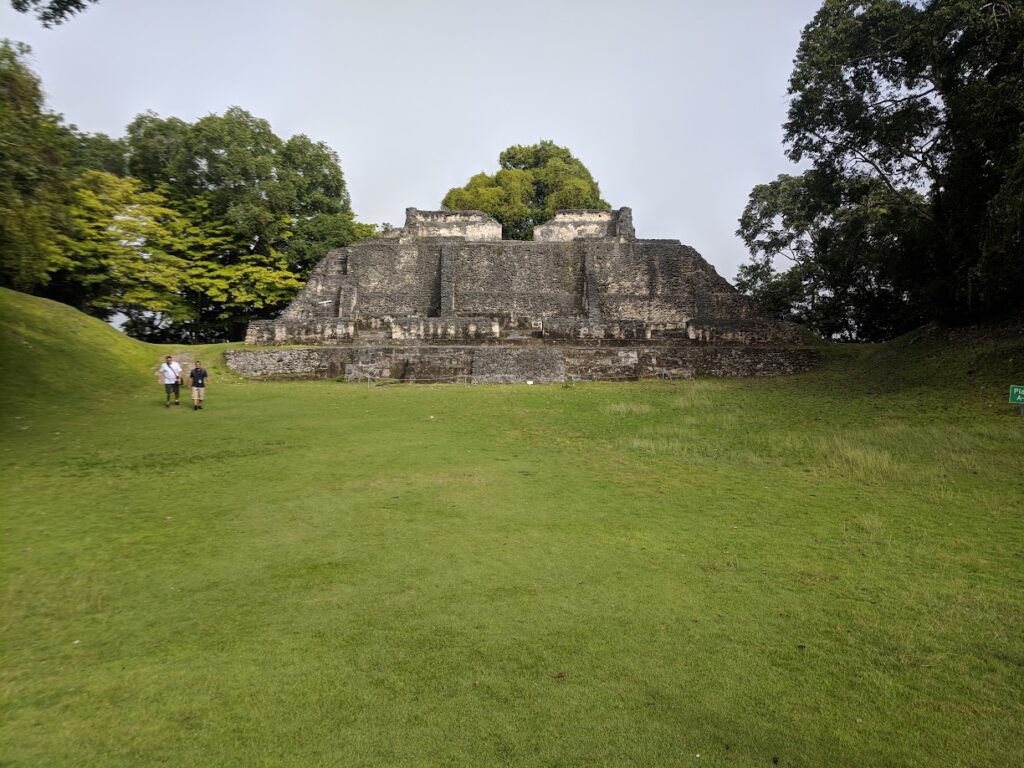

Archeologists believe Xunantunich was a ceremonial center between 600 and 800 AD. Like many other ancient Mayan cities, it is not precisely known what caused it to become abandoned, but the temples that have survived the onslaught of time still rise proudly into the mist.

El Castillo is the second tallest structure in Belize at 130 feet, and you are invited walk up its steps and view its royal chambers. The site is a repository of incredible artifacts, and previously undiscovered royal burial crypts have been excavated here as recently as 2006:

Archaeologists found the chamber 16ft to 26ft below ground, where it had been hidden under more than a millennium of dirt and debris.

Researchers found the tomb as they excavated a central stairway of a large structure: within were the remains of a male adult, somewhere between 20 and 30 years old, lying supine with his head to the south. In the grave, archaeologists also found jaguar and deer bones, six jade beads, possibly from a necklace, 13 obsidian blades and 36 ceramic vessels.

Epigraphers say the city’s ruler, Lord K’an II, recorded his defeat of another city, Naranjo, on the hieroglyphic stair, to go with his many other self-commemorations. On another work, he recorded a ball game involving a captured Naranjo leader whom he eventually sacrificed, according to the archaeologist Robert Sharer.

It is wrong to fixate on the violence that happened at sites like these. Westerners are quite adept at reducing a millennia of Mayan heritage down to its most sensational bits. This is an impulse we should have the maturity to avoid. All early human societies, by and large, celebrated violence and cruelty on a scale that is unimaginable to us now.

We are, of course, obligated to tell the truth about all instances of murder and ritualistic torture, but there is no human civilization without these sinister shortcomings. It is a scarlet letter all in our species must wear in equal measure. The brutality of early Mayan religion is certainly salacious, and no moral defense for it should be constructed.

One of the most enduring anthropology lessons I received during my time in Bible college was the universality of the pyramid as a human monument. Nearly all civilizations construct them, at some point, either as testaments to military victories or burial sites for revered leaders. Sometimes, these are known as ‘tumuli’ or ‘mounds’ and you can find them in Giza, Cahokia, Teotihuacan, even Sudan.

More broadly, though, monuments like these represent milestones in humanity – where language first begins to progress from glyphs into codified alphabets, where myths and generational storytelling is forged together into religious dogma. The sciences of engineering and arithmetic grow with each stone set into place, and humans that were once packs of nomadic hunter-gatherers now survive together in a city.

When I studied theology, we were taught about how organized belief almost always begins with agriculture. Farmers dependent on meteorology they could not understand or control will, eventually, turn to ritual. For comfort, for experimentation, for assignment of blame. It is a human impulse we all know well, and it haunts me throughout our journey.

At Xunantich, I am confronted again with the connection between the earliest human agriculture and a belief in the supernatural. There were certainly human skeptics that existed thousands of years ago as they do today, but without the benefit of the enlightenment, they would have gazed upon a hurricane or a tsunami and steadfastly concluded they had seen the hand of God. Usually, at this impasse – where weather and disease constitute an invisible and unknowable enemy – that most civilizations develop a religious doctrine of symbolic transference.

This is also a tenet of Judeo-Christian belief; that God is perfect, humans are not, and the thing that causes death, illness, and pestilence is sin. Thus, sinful humans must perform an act of transference, and on their account, a perfect being must suffer death, a punishment only reserved for the immoral. In Judaism, this took the form of livestock being slaughtered and its remnants immolated. The animal, and the practical resource it represented was sacrificed, destroyed in a ceremony meant to please a supernatural being. Their defining theological moment, in fact, is a pivot away from human sacrifice, found first in the story of Abraham being commanded not to murder his son. The fact this is considered noteworthy speaks to just how commonplace this practice was for nearly all ‘early’ religion.

The Maya believed a version of this, too. When illness or drought would descend upon their community, a sacrifice would be committed to please their gods, powered by the belief that the sickness that had taken up residence in the body could be transferred into the sacrifice, then killed. This follows the natural order, particularly in the observable world as they knew it. Resolution of a common problem, say, hunger, for instance, was comprehensively addressed by the death and dismemberment of an animal. Another being is sacrificed for the common good. Nearly all theology originates from this basic stem.

So, no, I do not gaze upon El Castillo with condescension. Nor do I regard it as the edifice of an exotic and blood-thirsty religion – because all religion was born from the same us-against-them mindset that always brings violence with it. What I choose to see instead is the wisdom and ambition of our ancestors, and I am filled with a longing to understand their stories more deeply.

Part III – San Pedro

There is infinite beauty in Belize. It is filled with thick green jungles that roll over dimpled hills and stumble into the blue-as-sapphire ocean for as far as your eye can see. It is an ecological cathedral, nearly unrivaled in its biodiversity, home to the largest unbroken barrier reef in the western hemisphere and the world’s only jaguar preserve. On this trip, I will see many wonders, but the drive inland was among the finest of them all. I don’t turn my nose up at a cruise or a resort, but if you never leave them, you will miss something very special indeed.

Bourdain warned all of us about the perils of the resort, and San Pedro very much falls under that umbrella. You miss key elements of the culture at the resort, he told us, and you turn the locals into indentured servants. You exchange vibrant music, nightlife, and food for the chicken nuggets of westernized blandness. I don’t dispute this entirely, but I think there is a time and a place for a resort, and I don’t begrudge those who choose that path for their travels. San Pedro does carry with it all of the usual accoutrements of a resort town, and in that context, there is little accounting for taste, and I say this all without judgement.

One of the cornerstones of Post-Cold War communist ideology revolves around Washington’s chew-toy treatment of the Caribbean and South America. The United States spent billions bullying Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, among many others, only to see those nations become more even militant and impoverished. There is little to show for decades of aggressive foreign policy, and the quality of human life, with some exceptions, diminishes greatly below the equator.

Belize, like many other states in the southern hemisphere, is beset with social and economic challenges. Poverty in this country is extreme, and many of the locals are suffering every day. Belize shares a border with Guatemala, and it is here that many begin an arduous journey that will take them, often on foot, through the entire length of Mexico, hoping against hope that the United States will not send them back.

Once we reached the island, I watched as the ferry operators unloaded cases of bottled water as their passengers departed. No fuel seems to go to waste here, and where there’s an extra dollar to be made, by God, they’ll make it. The local plugs were ready and waiting for new clientele, offering us ‘special brownies’ within moments of our arrival. The informal economy swings into action like a well-oiled machine, and up close, it’s a hell of a sight.

The DEA claims more than 600 tons of cocaine travels through Central America each year. Belize, with its dense jungles and low population density, make it an ideal trafficking spot for all manner of illegal cargo. Tourist hubs are often one-stop shops for organized crime, as they offer traditional ports and distribution centers alongside transient and cash-holding clientele who are looking for a good time abroad. These illicit industries are not benign, and they leave a trail of human misery wherever they set up shop.

UNICEF estimates 6 out of 10 Belizean children do not have access to one of the following: “adequate nutrition, clean drinking water, proper sanitation, or access to education.” Nearly 50% of all children under the age of 15 are classified as ‘poor’ and 58% of children under the age of 18 are ‘multi-dimensionally poor,’ a designation reserved for people who, in addition to being impoverished economically, are also deprived of access to education and basic infrastructure. No money, no school, no hospital, and nowhere to turn.

Tourism does bring foreign money, yes, but it can also limit upward economic mobility for an already fragile middle class. Spikes in tourism often necessitate sudden foreign investment on bad terms, and these kinds of transactions can actually suppress local industries most in need of patronage. The country is caught in a tug-of-war between the cartels and the cruise ships.

We are openly offered more drugs at least two or three more times on the island. Belize plays a key role in the global logistics of narcotics trafficking. When the notorious cartel kingpin ‘El Chapo’ was first apprehended, he was in possession of three passports – one Mexican, one Honduran, and one Belizean. You will see gaggles of teenage boys with golden watches, custom trainers, and uncommon modern fashion and you will not need to wonder what business they are in. At multiple junctures in our journey, we get the sense we are being sized up; what sort of fun are you after in this tiny country? How much money do you really have?

Part IV – Kayaking

I am fond of adventurous girls. They can come with some downsides, though, like on this occasion, where she confidently paddled us into what Google would describe as an active shipping lane. The presence of passing ferries and container ships did not shake her conviction that we had not gone out too far. The line between ‘fun dinner party anecdote’ and ‘hospitalization in a foreign country’ can be very fine indeed.

A vacation, on some level, is an exploration of one’s relationship with danger. Each choice made in the pursuit of recreation abroad represents a calculation of risk. This is why I am reluctant to judge how others choose to travel. Some might turn their noses up at a cruise or a prolonged stay at a resort, and these options are quite popular choices in this part of the world.

In my mind, I could only imagine the danger that awaited us the further we went from the safety of the shore. This fear was valid, and dutifully confirmed by the GPS chip inside of my phone, which provided critical ammunition for the marital argument that followed our amateur nautical excursion.

But maybe her danger calculation was just different than mine. Not wrong, not right, just hers, and hers to make. After all, hadn’t we just explored the ATM cave, beset with snakes and whip scorpion spiders? (do an image search for those at your own peril.) Wasn’t it a bit rich for me to moan about danger at just the moment she felt like exploring further?

That night, I am no worse for the wear. Just sunburned, exhausted, drinking cocktails and eating fried food on the beach. The moon is full, its light cold, bone white, rays bouncing off gentle waves, sparkling like diamonds. Sea breeze subtle as silk grazes my cheek. A beautiful woman sits opposite me and smiles. There isn’t much more any man could ask for, and I thank the stars for my good fortune.